It was the closest election in American history.

In the prior 16 years, the country had undergone a political, social, and technological transformation. American society was nearly unrecognizable to its previous forms. The nation once split by Civil War was now whole again, slavery had been abolished, Black men could vote and held hundreds of political offices across the country, women’s suffrage was gaining steam, and new inventions like the telephone, typewriter and electric light were beginning to change life as people knew it.

However, in America, progress isn’t linear.

At the end of the war, Union troops remained in the South to tamp down political terrorism, and by 1876, the troops were still there in three Southern states: Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida. The continued military occupation in the reconstructed South along with the unease brought on by an economic depression caused voters to question the vision of a Republican Party that rode into power with Abraham Lincoln and the promise of a vastly expanded and more muscular federal government in 1860. After Lincoln’s assassination, his Vice President, Andrew Johnson, took office. Johnson had been the lone Southern Democrat in the Senate to remain loyal after secession—and as a show of unity, he became Lincoln’s running mate in 1864. However, Johnson’s disregard for Reconstruction and the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments which gave Black Americans freedom and equality before the law, along with Black men’s right to vote, led to his impeachment in the Republican-held House and near conviction in the Senate.

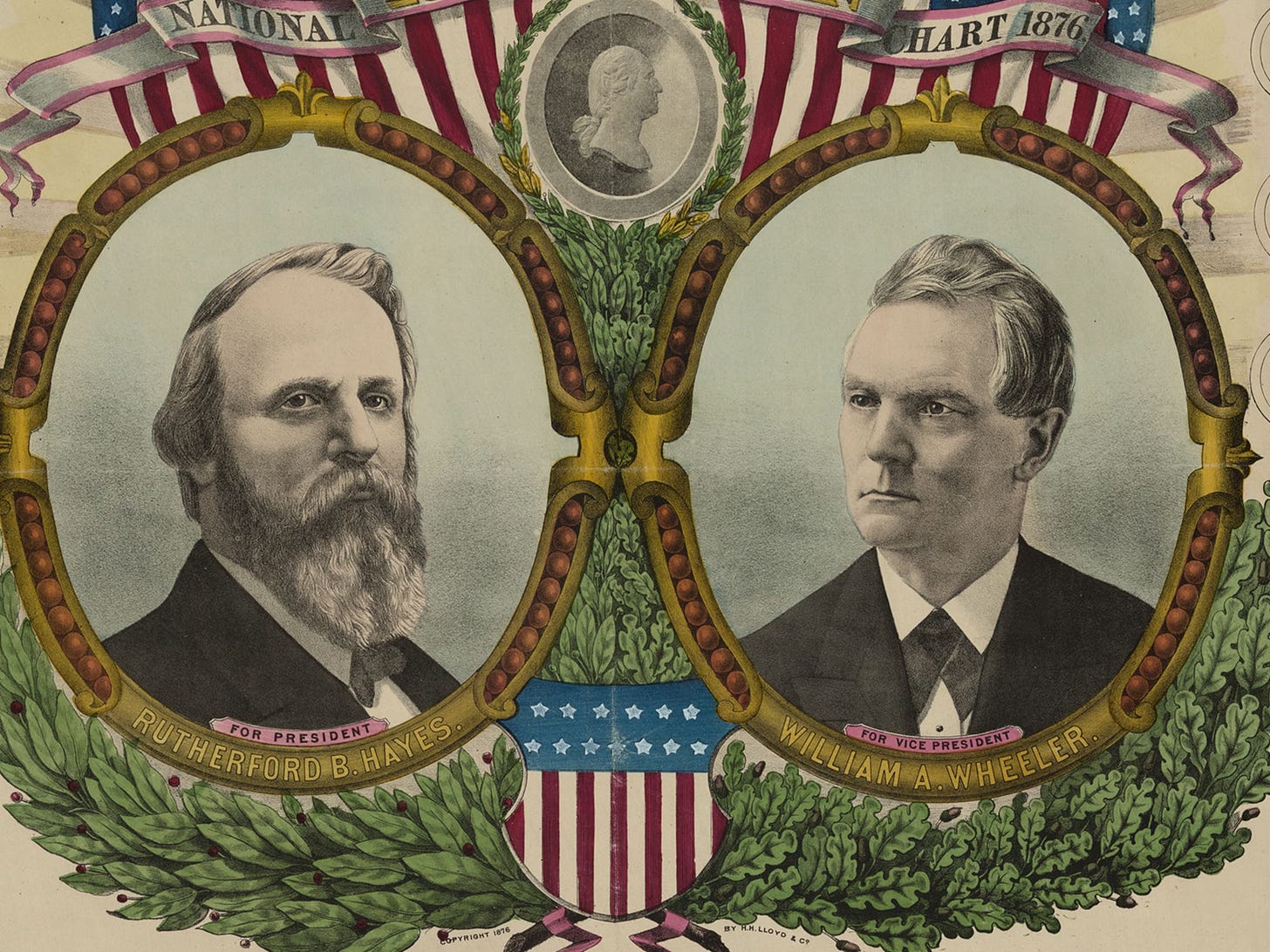

In 1868, free of Johnson, Republicans nominated General Ulysses S. Grant, who restored the promise of Reconstruction and sailed to two terms in the White House. He maintained the commitment to Reconstruction and passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875. However, in the intervening years, Southern opposition to federal occupation had grown more violent. On the day Republicans nominated their new candidate in 1876—Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes—a race riot broke out in the town of Hamburg, South Carolina when a terrorist group known as the “Red Shirts” broke up a parade of Black militia men celebrating the American centennial. A confrontation occurred without violence—until four days later, when the Red Shirts surrounded the militia headquarters, and warned, “this is the beginning of the redemption of South Carolina.” Their vision of redemption became clearer when the Red Shirts captured 25 of the Black militiamen and executed five of them in cold blood, just days after the men had gathered to celebrate America’s 100th birthday.

The violence wasn’t random but part of a new political strategy in the South, one intent on restoring “home rule” to former Confederates. While new laws called “Black Codes” implemented poll taxes, literacy tests, and Grandfather clauses to prevent Black Southerners from voting, many white Southerners still felt aggrieved by the fact that they had lost the Civil War. To restore the racial order they sought, many went beyond the law, beginning in 1875 when the Red Shirts implemented “the Mississippi Plan” to intimidate Black and white Republicans from voting, and ousted Republican Governor Adelbert Ames. Soon, the plan was adopted across the South for the presidential election the next year. As one South Carolinian said, the idea was for each Democrat to “control the vote of at least one negro by intimidation,” and to understand that “argument has no effect on them: they can only be influenced by their fears.”

By the end of Election Day in 1876, it appeared that the campaign of violence had worked: returns indicated that the Democrat, New York Governor Samuel J. Tilden, had won. However, after a review of the balloting it became clear that there had been widespread fraud, especially in the South, where it appeared Tilden and the Democrats had won multiple states for the first time since 1856, the last election prior to the Civil War. But in three Southern states—Louisiana, South Carolina and Florida where federal troops remained to maintain free and fair elections—Hayes appeared to hold onto victory. Still, even after a recount, a winner was not clear.

Soon thereafter, Congress created an independent electoral commission to investigate the fraud made up of ten congressmen, divided between both parties, and five Supreme Court justices. After discussions—including the resignation of one Justice who had recused himself after winning election to the Senate as a Democrat, only to be replaced by Republican Justice Joseph P. Bradley—Hayes was named the winner by an 8-7 margin.

However, the fight wasn’t over. Southern Democrats threatened to obstruct the final House proceeding and some feared the trigger of secession or even a second Civil War.

From the beginning, Hayes had been aware of Southern Democrats’ aims. On the day after the election—when it appeared that he had lost—he wrote a friend, lamenting that the Reconstruction Amendments would be treated as “nullities, and then the colored man’s fate will be worse than when he was in slavery.” But now Hayes had been called the winner—and desperately sought to avoid further turmoil.

So, he made a deal.

He would become the President—and federal troops would leave the South, thus turning a blind eye to whatever it was that Southerners planned to do in the Old Confederacy they sought to “redeem.” Rather than seek reconstruction, the Republican Party—the party of Lincoln, the party of emancipation, the party that saved and preserved the Union—would leave the South and turn its focus on expanding business in the United States. It would become the friend of corporations, rather than the freed.

Hayes wouldn’t seek the presidency in 1880, but a Republican would win again, James A. Garfield, without a single Southern state. In fact, after Hayes, a Republican wouldn’t win a single Southern state until 1920—and a Republican wouldn’t win Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida all together again until Nixon in 1972. By returning power to the Old Confederacy, Hayes ended Reconstruction and turned the page in American history. He capitulated to the same powers that Lincoln and Grant had defied—to the same powers that caused a Southern rebellion and a war to preserve slavery, in which 700,000 Americans died. He, and the Republican Party, turned their back on the very promise of expansive freedom in the United States.

The Civil War was over. The South had won.

Sources:

Eric Foner. Reconstruction. 1988.

Rayford Logan. The Betrayal of the Negro. 1954.