One-two-three four!

One-two-three-four!

America needed a distraction—and it found one in a cold television studio on an early February evening. Exactly 79 days prior, two seminal events had happened on November 22, 1963. That afternoon at 12:30 PM local time in Dallas, President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated while his motorcade rode through Dealey Plaza on its way to the Dallas Trade Mart. The ensuing days and months had been a waking nightmare. The first President born in the 20th Century—just 46 years old, the father of two young children—was dead and along with him, it seemed, the promise and possibility of the American Century. But another thing had happened that day, thousands of miles from Dallas, far across the Atlantic: a British band that few Americans had ever heard of released an album called With The Beatles. The record’s first track seemed to be a promise: “It Won’t Be Long.”

That night—just about the time Air Force One took off from Love Field with its nose pitched skyward—the Beatles played a concert in Stockton, England at the Globe Theatre. The night before they had played Carlisle, and the next day they played Newcastle. By that point, the group was one of the most experienced acts in all of music. That year, they played 258 live shows. It was just another year for the group. Between 1961 and 1963, the Beatles had made 292 appearances the Cavern Club in their hometown of Liverpool alone. But it wasn’t Liverpool but Hamburg, Germany where the band had really cut its teeth. In Hamburg, in those same years, the Beatles played over 1,200 separate shows, seven days a week, often for 6 to 8 hours across multiple shows a day, honing their act in front of crowds born and raised during the Third Reich.

By the time the Western Cartridge 6.5 x 52mm round nose bullet left Lee Harvey Oswald’s Carcano Model 38 rifle atop the sixth floor of the Dealey Plaza book depository, the Beatles were already the number one selling artist in Britain. The very next day—November 23, 1963—it was announced that the Beatles first LP, Please Please Me, had reached #1 in the U.K. for the 29th straight week. Still, however, the band had little American exposure or radio play. Briefly, the title track to “Please Please Me” ran on WLS in Chicago in February and KRLA played “From Me to You” in Los Angeles in May, but neither generated much interest. Then, on December 10, 1963—while the flags around the nation were still at half-mast to honor the slain president—the CBS Evening News ran a five-minute segment that had been scheduled to run on the evening of November 22, a segment which was bumped by breaking news coverage of the assassination.

That evening, as mothers, fathers, daughters and sons gathered around the television, one particular young girl was paying closer attention than most. Her name was Marsha Albert, a 15-year-old who lived in Silver Spring, Maryland. She immediately wrote to Carroll James, a disc jockey at her local station, WWDC-AM, “Why can’t we have music like that here in America?” James started making calls and soon a copy of “I Want To Hold Your Hand” was in the carry-on of a British Airways flight attendant, on its way to Rockville, Maryland of all places, where WWDC-AM was stationed. On December 17, James invited Marsha Albert to introduce the song on air.

Lightning had struck. After the overwhelming response, Capitol Records president Alan W. Livingston rushed the single for national release on December 26, 1963. Within ten days, the single sold over one million copies. At the same time, on January 8, President Johnson addressed the 88th Congress in his first State of the Union address. He told those gathered, “Let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined.” And it was—by June, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would be passed, ending legal racial segregation in America. America was changing—quicker than anyone realized. Eight days after President Johnson’s address which called for the most consequential domestic legislation package in over 30 years, the Beatles checked into the George V Hotel in the heart of Paris’ 8th arrondissement. As they entered their rooms, a telegram was waiting for them: “I Want to Hold Your Hand” had reached Number One in the American charts. Four days later, With The Beatles would be released in America as their first U.S. LP, under the new name, Meet the Beatles. Within fourteen days it would be certified gold.

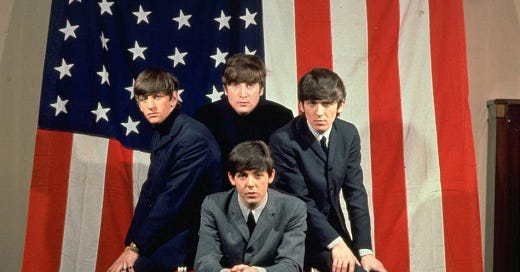

Still, though, the four Beatles themselves had never stepped foot in America. What visions of glory they must have had—through all the work they put in, all the shows at the Cavern Club, all the beer-soaked nights in Hamburg, even they must have been amazed. Ringo Starr and John Lennon were both 23 years old. Paul McCartney was 21, and the youngest of the four, George Harrison, was 20 years old. Now, they were on the precipice: the Beatles were coming to America, in the flesh.

All the while, the Beatles had been the benefactor of incredible timing. Acts that had come before them, like Elvis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, and Buddy Holly had all laid the groundwork in America—but still, America had never seen anything like this. And all the more, their timing was about to get better. Because in early November—while President Kennedy was still alive and they were still unknown—their manager, Brian Epstein, had scheduled the band to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show on CBS in early February. Epstein had no idea that girls like Marsha Albert were out there in places like Silver Spring, Maryland or that America was about to lose its young, radiant president and yearn for something to heal their pain. Someone to hold their hand.

On Friday, February 7, 1964, Pan American Flight 101 arrived from London Heathrow to New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport—which had been renamed from Idlewind Airport to JFK exactly one month after the President was killed. Crowds numbering in thousands were waiting—to watch them, to take photographs of them, to scream their names—and to follow them, everywhere. After an introductory press conference, the Beatles arrived at the Plaza Hotel.

Two nights later, on Sunday February 9, after Ed Sullivan’s stilted introduction, a record television audience of 73 million Americans saw them: The Beatles. Paul McCartney turned to the rest of the band, “One-two-three-four!” And then came the words that acted like a salve for millions: “Close your eyes, and I’ll kiss you…” After “All My Loving” the band played “Till There Was You” and then “She Loves You” as the screams of the girls in the audience began to drown out even the television microphones. Across America, boys and girls, young and old, were jumping around their living rooms amazed by the bowl-cutted, black-suited foreigners that had changed their lives in an instant. If President Kennedy had brought their black-and-white world into living color, the Beatles now provided the soundtrack.

After an ad break, the Beatles were back. First, “I Saw Her Standing There,” as the crowd teetered on pandemonium, as each Beatle never dropped his smile—always seeming to know where the camera was angled. Then the finale—that opening riff, the harmony vocals, the bouncing bass, the drive of the drums—“I Want to Hold Your Hand.” For a moment, the center of the universe was inside the Ed Sullivan Theater in New York City. For a nation rocked by grief and uncertainty, here they were—as unlikely a group as ever, four kids from Liverpool, making a promise that millions wanted to hear:

Oh, yeah, I'll tell you somethin'

I think you'll understand

When I say that somethin'

I want to hold your hand

…I want to hold your hand…I want to hold your hand.

Sources:

http://www.dmbeatles.com/history.php?year=1964&month=2

https://beatles64.com/p/beatles-paris-behind-iconic-1964-residency-part-1

https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/lyndon-b-johnson-event-timeline

I was in the sixth grade. I still remember when the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan show and all my friends were buying magazines with stories about the Beatles. Thanks for the memory.

Very interesting that a request to a radio station from a young fan may have changed the history of the Beatles.