It was a premeditated political stunt. The host didn’t know it, the audience didn’t know it, the media didn’t know it (and took too long to catch on), but the candidate knew exactly what he was doing. A white candidate speaking out on race to a Black audience—nothing a political consultant would advise.

But here he was, and he was a different kind of politician: one who flew into storms of controversy rather than around them, and incredibly—to the dismay of his detractors—seemed to weather them unscathed.

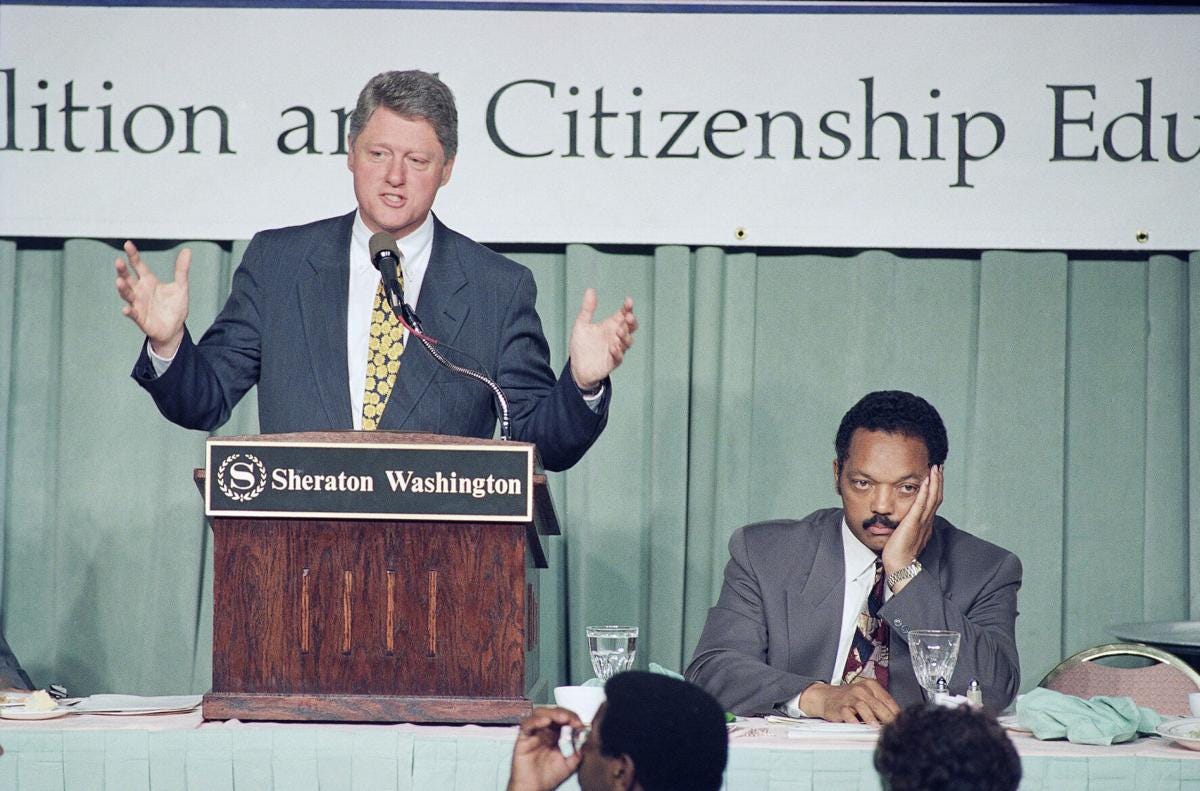

It was June 13, 1992 and the presumptive Democratic nominee, Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton had come to an event hosted by the Rainbow Coalition and the Reverend Jesse Jackson. Jackson was the living embodiment of the continuing Civil Rights odyssey in America. He had marched at Selma, he had helped take Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s movement to Chicago—he had even been with Dr. King at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis when he was killed. In the years in between, he had made a name for himself on the national stage, finishing third in the 1984 Democratic presidential primary and second in 1988, winning nearly 7 million votes. By 1992, Jackson was probably the most influential Black person in American politics. But that year he had decided to sit the race out—many of the rumored aspirants had.

Potential frontrunners like New York Governor Mario Cuomo and Senator Bill Bradley refused to run, the thinking went, because incumbent President George H.W. Bush was so popular. After the swift US victory in the Persian Gulf War in early 1991, Bush’s approval rating was a sky-high 89 percent. Republicans had won 5 out of the prior 6 presidential contests—and in 1988, Bush had caricatured his opponent, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, as too liberal, too “weak on crime,” framing Democratic positions as 1960s-styled fantasies that increased spending on social programs.

In 1985, a group called the Democratic Leadership Council was founded to reverse this trend by pushing the party further rightward. Founded by Al From, who had long sought Clinton as the kind of politician he thought could lead such a movement, the DLC sought “a bloodless revolution in our party” as conservative organizations like the Heritage Foundation and Cato Institute had succeeded in doing in the GOP during the 1970s and 80s. At the 1990 gathering in New Orleans, the organization declared that “the political ideas and passions of the 1930s and 1960s cannot guide us into the 1990s” and that the mission of the party was to “expand opportunity, not government.” The DLC pushed many Democrats away from the thinking of Jesse Jackson—who pushed for an expansion of Great Society policies rather than a retreat—and toward a greater focus on “northern white ethnics and southern white protestant males—whom they deemed ‘the heart’ of the electorate.” In response, Jesse Jackson said that DLC actually stood for “Democrats for the Leisure Class.”

But the DLC was winning, and Jackson was losing. In fact, the wave of resentment which had been cascading for decades had not yet crested. And in June 1992—the wave may have been gaining steam. In 1991, the violent crime rate had skyrocketed to its highest point in American history. America was on edge. And just weeks prior to Clinton’s speech to the Rainbow Coalition, the nation had been rocked by the largest riots in American history. On April 29, 1992—about ten minutes after four LAPD officers were acquitted for the brutal beating of Rodney King—crowds began gathering at the Pay-Less Liquor and Deli on Florence Avenue in South Central Los Angeles. Soon, the protests turned to riots. Over the next five days, over 10,000 National Guardsmen were deployed, over $1 billion in property damage was caused, and over 50 people died.

Since the Watts riots in 1965, Los Angeles had remained a tinderbox, fueled by a cocktail of low employment opportunities, zero tolerance policing, and massive cuts to social spending in predominantly Black neighborhoods like South Central. As businesses and jobs moved out, gangs and drugs moved in—along with increasing numbers of police officers who served as a de facto occupying army. LAPD units like “Total Resources Against Street Hoodlums”—or TRASH—were created to patrol Black neighborhoods. The number of businesses went down as the number of police stations went up. After the King acquittal, the tinderbox blew up.

Clinton was watching. He wasn’t going to make the same mistakes as Dukakis. He was going to reject the legacy of the Great Society, reject an expansive federal government, in other words, reject Democratic Party orthodoxy. Instead of appealing to the middle as many nominees do, Clinton in fact would go right of his opponent, President George H.W. Bush, as much as he could.

Earlier that year, Clinton had left the campaign trail to directly oversee the lethal injection of Rickey Ray Rector, a convicted murderer with the cognitive function of a child. Shortly after that, he gave a press conference at Stone Mountain in Georgia—the site of the Confederacy’s version of Mount Rushmore. But it wasn’t just so much what he stood in front of as who stood behind him: about 40 mostly Black inmates from the local state correctional facility who did work on the monument’s grounds. In the press conference photo op, they stand in a few single-file lines, their hands behind their backs, dressed in crisp white jumpsuits and hats. The perfect portrait of racial dominion. As Clinton’s 1992 primary challenger, Governor Jerry Brown, said at the time, “two white men and forty black prisoners, what’s he saying? He’s saying ‘we got ‘em under control, folks.’”

Then Clinton got a chance to go further. In the wake of the riots, an obscure rapper named Sister Souljah—who happened to speak the prior night at the same Rainbow Coalition conference—made headlines when she gave an interview to The Washington Post. A Rutgers graduate born Lisa Williamson, Sister Souljah gave a wide-ranging interview, speaking in pained detail about the anxieties of Black America in the wake of the riots. But then she said the line that launched a thousand op-eds, “I mean, if Black people kill Black people every day, why not have a week and kill white people?” Predictably, the circus moved in.

Governor Clinton had his mark. Speaking in front of a mostly Black audience at the Rainbow Coalition, Clinton had only one voter in his mind: the white moderate who had seen the montages of the riots in South Central Los Angeles, who had read the Sister Souljah quotes in the newspaper, and faced now a choice between a WWII-veteran President, a straightlaced Texas businessman (Ross Perot), and a pot-smoking, adulterer who wore his hair to his shoulders when he attended Yale Law School. After his perfunctory thanks yous and talking points, Clinton then said it was time to “stand up for what’s always been best about the Rainbow Coalition, which is people standing up across racial lines.” Then he pivoted: “you had a rap singer here last night named Sister Souljah,” going to directly quote her comments in The Washington Post, and expanding on prior comments which stated, “if there are any good white people, I haven’t met them—where are they?”

Clinton answered: “Right here in this room. That’s where they are.” He went on, “if you reversed the words white and black, you might think David Duke was giving that speech,” in reference to the former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard who had nearly been elected Governor of Louisiana in 1991. Then Clinton got to the heart of it: “we can’t get anywhere in this country pointing the finger at one another across racial lines,” a rich accusation considering it could be figured that was exactly what Clinton was doing.

In the aftermath, Reverend Jackson knew what Clinton had done, accusing it was to “purely appeal to conservative whites.” Jackson was right: he had been used. His waning popularity among moderate voters was exactly the platform Clinton wanted—a negative to hold himself up against, a comparison to illustrate that which he was not. And it worked. Clinton won 48% of moderates, over Bush’s 31%, capturing the group that had long eluded Democrats. But he also won historic margins of Black voters, who arguably delivered him the election.

Last week, one candidate tried to make a similar swing when he questioned the racial identity of his opponent in front of an audience of Black journalists. Despite the fact that the comments appeared to be bigoted psychobabble, it’s obvious they were purposeful. And while it’s clear that one candidate still believes we live in the political age that began 32 years ago, it’s not as obvious if the results will bear out as they did in 1992.

But then again, only those listening for it can hear a dog whistle.