Newt's World

Mechanisms of Control

The 1951 science fiction novel, Foundation, by Isaac Asimov, takes place far into the future, in a world in which the vaunted “Galactic Empire” has fallen into a period of irreversible decline. Nobody in the Empire can see the imminent fall yet—except for an old sage named Hari Seldon, who has developed a theory called “psychohistory” that predicts momentous events before they happen. While Seldon dies early in the story, he leaves behind a series of plans for others who work to prevent the Empire’s collapse. At the moment of the book’s publication, there was a nine-year-old boy living above a gas station in Hummelstown, Pennsylvania looking to save the world, too. But first he had to escape his own.

The boy lived with his mother, who spent most of her time on pills, and his stepfather, an Army officer who didn’t spend any time with him at all. His biological father gave him his first name and not much else. In fact, he had abandoned the boy’s mother, then just 16, shortly after she became pregnant. So the young boy who lived above the gas station read to escape. He read Asimov’s books, all of them, along with most everything else he could find, including the histories of his own world. In time, he developed into a chubby, unpopular kid with coke-bottle glasses who seemed to know something about everything except how to make a friend. His name was Newt Gingrich.

In 1958, Gingrich’s life had forever changed. He was 15 years old, living at an Army base in France, when the family visited Verdun, the site of the longest battle of World War I which resulted in 700,000 combined deaths. At Verdun, he realized that an Empire’s collapse wasn’t restricted to Isaac Asimov books. In a story Gingrich would repeat again and again in the future, he said, “Over the course of the weekend, it convinced me that civilizations live and die by, and that the ultimate margin in a free society of our fate is provided more by, elected political leadership than by any other group. That in the end, it’s the elected politicians that decide where we fight and when we fight and what the terms of engagement are, and what weapons systems are available.”

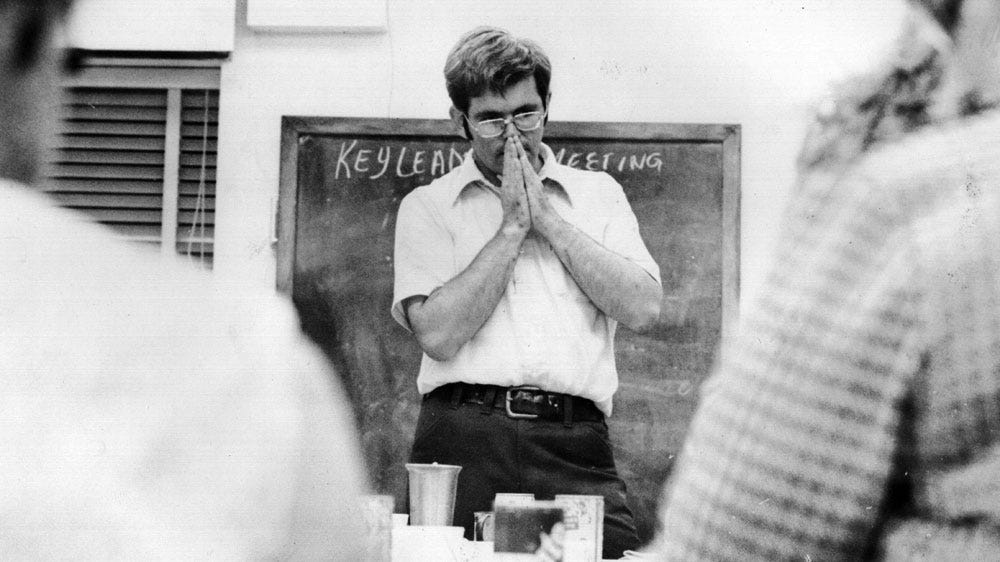

Eventually, his stepfather was stationed at Fort Benning, and Gingrich spent the rest of his early years in Georgia. He went on to Emory, then Tulane, where he received his Master’s and PhD in European history. He then became a history professor at West Georgia College, staying on top of the political scene as he kept reading and digesting an America that was changing before his eyes. He had seen Camelot become the Great Society, all only to be replaced by Nixonland. By the 1970s, America was at odds with itself, as the once inimitable empire watched its President resign in disgrace, while its world-conquering Army suffered loss after loss in the tangled jungles of Southeast Asia. Surely, some solution was at hand. Surely, someone could save the Empire. Newt Gingrich, like Hari Seldon before him, believed he could presage what lay ahead. Around that time, he wrote on a blackboard in his classroom:

Gingrich—primary mission

Advocate of civilization

Definer of civilization

Teacher of the Rules of Civilization

Arouser of those who Fan Civilization

Leader (Possibly) of the civilizing forces

A universal rather than an optimal Mission

Gingrich saw his future: a seat in the U.S. House, the Speakership, then the Presidency, and most importantly, a total reorientation of American society. He ran in 1974 for the House as a Republican and lost like most other Republicans amid the Watergate backlash. Democrats had a wave election that year—except for another young Southerner named Bill Clinton, who ran for Arkansas’ 3rd Congressional District, only to lose. In 1976, Gingrich ran again and lost again, this time because Georgia’s own Jimmy Carter carried the state and the White House. In 1978, President Carter began to falter as the country suffered from what Carter called a “crisis of confidence.” Gingrich called it the inevitable failing of “the corrupt liberal welfare state.” He ran again. This time, at 35 years old, he won.

This time his message was much more dramatic. As he told a group of Young Republicans that fall, “You’re fighting a war. It is a war for power.”

In 1978, a cast of new names entered high offices. Gingrich went to the House, alongside others like Dick Cheney from Wyoming and Dan Quayle from Indiana while former Princeton and New York Knicks star, Bill Bradley, entered the Senate. In Arkansas, 32-year-old Bill Clinton was elected Governor. By then, Gingrich had found his own theory that he believed could prevent the American empire’s collapse and win the future for his side. It was language itself. More so than his peers, Gingrich realized that the ways to speak—and where to get noticed—had changed. Shortly after his arrival in the House, C-SPAN turned on its cameras, turning American politics into a television spectacle. While few noticed immediately, Gingrich did. He would give rousing, existential speeches to an empty floor, knowing full well that the cameras were only focused on the lectern.

In genteel Washington—a place in which President Reagan, a Republican, and Speaker Tip O’Neill, a Democrat, regularly clinked glasses—nobody fully understood that there was political currency in demonizing one’s opponents. Perhaps other than the booze-fueled days of Joseph McCarthy, no elected official had been so overt. That is, until Newt Gingrich came along. He understood that, in a changing media environment, controversy and life-or-death rhetoric sold and gained headlines, whereas talk of compromise was left to the back pages.

Beginning in 1990, after Gingrich became House Minority Whip, he used the political action committee GOPAC to distribute pamphlets, videos, and audiotapes to Republican candidates on how best to engage. The best example was the memo, “Language: A Key Mechanism of Control,” which he prepared along with the pollster Frank Luntz. It began, “As you know, one of the key points in the GOPAC tapes is that ‘language matters.’” It continues, describing the plea heard across the GOP, “I wish I could speak like Newt.” As the memo says, “That takes years of practice. But we believe that you could have a significant impact on your campaign and the way you communicate if we help a little. That is why we have created this list of words and phrases.”

The words and phrases included “decay, failure (fail), collapse(ing), crisis, sick, pathetic, lie, waste, corruption, incompetent, traitors” and so on. This is how Gingrich wanted Republicans to describe Democrats—in existential, black and white terms. And on the flip side, he wanted Republicans to describe their own program using words like “opportunity, legacy, liberty, commitment, principle(d), lead, vision, success.” As the memo noted, “The words and phrases are powerful. Read them. Memorize as many as possible. And remember that like any tool, these words will not help if they are not used.”

It was all part of what Gingrich had said back in 1978: that politics is a war for power.

In addition to the literature, Gingrich’s interviews made for a modern-day Art of War in their own right (unsurprisingly, one of Gingrich’s favorite books). He said his goal was “reshaping the entire nation through the news media” while pointing out that “fights make news.” After the 1994 elections in which Republicans won the House for the first time since 1952, Gingrich said giddily, “I am learning that everything I say has to be worded carefully and thought through at a level that I’ve never experienced before in my life.” He had created an entire world of politicians who acted like him, thought like him, and spoke like him. As future Speaker John Boehner said, “If it weren’t for the [GOPAC] tapes, I probably wouldn’t have run for Congress.”

In 2025, we’re living in Newt Gingrich’s America.

More than Donald Trump, Barack Obama, Rupert Murdoch, or Rush Limbaugh, Newt Gingrich—the chubby kid who found refuge in sci-fi books—created the political environment we now inhabit. While he described the major political victory of his career in 1994 as “a first step towards renewing American civilization,” his real world-making skills can be felt in the present.

A few weeks ago, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said, “The Democrat Party’s main constituency is made up of Hamas terrorists, illegal aliens, and violent criminals.” Even the subject of the sentence—the “Democrat” Party—is a use of language as a mechanism of control. For a few years now, Republicans have used the term to strip Democrats of the small-d democracy affiliation, while the rest of the sentence is a version of what Gingrich prescribed in 1990, but to the nth degree. Even then Gingrich advised Republicans to describe Democrats as “traitors.” Now, they are described as terrorists. Over a 35-year period—beyond being a harmful lie—it’s a natural progression of language.

Donald Trump’s use of “Little Marco,” “Low Energy Jeb,” and “Crooked Hillary” in 2015 only scratched the surface of insults that he has leveled over the last decade. Then and now, Trump’s mastery of put-downs has felt original. But at their core, those names, much like Stephen Miller’s recent characterization that “The Democrat Party is not a political party, it is a domestic extremist organization,” are a natural extension of the world Gingrich created through the weaponized deployment of language in politics. Remember: “You’re fighting a war. It is a war for power.”

Gingrich, in one sense, did not accomplish his goals. He never became President and has not been the “Leader (Possibly) of the civilizing forces” as he wrote on his classroom’s blackboard. But presidents come and go. Few of us can list off hand the ways in which George H.W. Bush or Jimmy Carter changed the American experiment. But Newt Gingrich has. The boy who grew up above the gas station has become the “Definer of civilization,” and the “Arouser of those who Fan Civilization,” and to our national detriment. He has, over the course of 35 years, changed not only how politicians—but increasingly, how everyday Americans—speak to each other using a lexicon of hate and division. As Gingrich once said, “I have an enormous personal ambition. I want to shift the entire planet. And I’m doing it.”

Sources:

George Packer, The Unwinding (2013). Chapter on Newt Gingrich, p. 19-25.

https://theamericanleader.org/timeline-event/politics-is-a-war-for-power/

https://fair.org/home/language-a-key-mechanism-of-control/

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/newt/newt78speech.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1990/09/09/us/political-memo-for-gop-arsenal-133-words-to-fire.html

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/newt/boyernewt1.html

Newt Gingrich changed the Republican party from being a representative of business and taxpayers into a reinterpretation of the confederacy. In 1994 I was president of a Kiwanis Club, a church officer and, as now, a small business owner. I was also a twenty-year Republican, and left that party because of Gingrich’s promise to divide and conquer the country I loved. I lost a lot of “friends” over that change. They simply did not see it the way I did — that our exceptionalism comes from the vote.

There is a straight line between the politics of Newt Gingrich and the presidency of Donald Trump. He has committed his party to a wiin/lose situation - and they seem to be losing. Time will tell. Newt can watch from hell.

Perfect! Keep telling our history to all the generations. When former GOP members, the anti-Trump conservatives, kept shouting at Democrats to fight more like Republicans, I always thought of Gingrich (and Tom DeLay). I'd say, "We don't want to be like them!" It strains credulity that he thought he was a civilizing force. More of a Hobbesian force. Thank Tim.