The brown-paper package, eight by eight inches and one inch thick, had a Florida postmark and no return address.

For 45 days, it had been sealed—traveling from Washington, D.C. to Miami, where it was deposited into an outgoing mailbox on November 21, 1964, and then snaking through the U.S. Postal System, to 234 Sunset Avenue in Atlanta, Georgia, a modest brickhouse along a sleepy, treelined street just west of the city’s growing downtown. For weeks the package sat dormant inside the house, among many others that had gathered on the home’s porch, the remnants of a busy and tormented prior year for the family who lived inside.

Inside the package was an unsigned letter—and a tape reel. The letter was a direct threat to the recipient, alluding to the contents of the audio on the tape: “You are a colossal fraud and an evil one at that…Like all frauds your end is approaching…No person can overcome facts, not even a fraud like yourself. Lend your sexually psychotic ear to the enclosure…You are finished…It is all there on the record, your sexual orgies. Listen to yourself you filthy, abnormal animal…You are done…There is only one thing left for you to do. You know what it is…You are done. There is but one way out for you. You better take it before your filthy, abnormal, fraudulent self is bared to the nation.”

The letter’s intent was clear: for its recipient, The Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr., to kill himself.

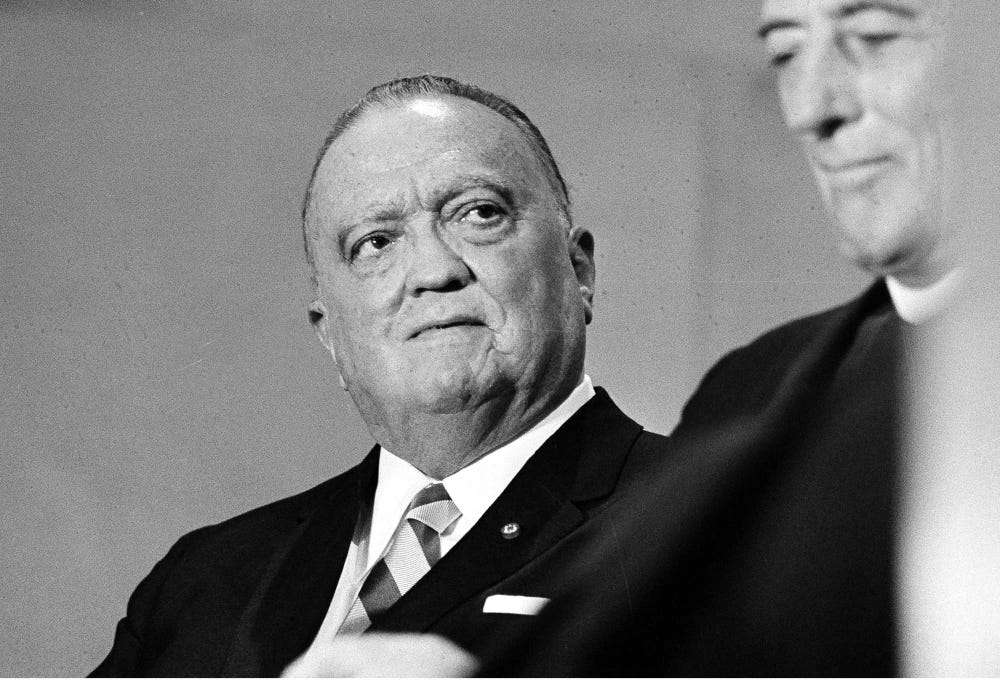

The package had been put together and the letter written by William C. Sullivan, the head of intelligence at the Federal Bureau of Investigation under director orders from his boss, J. Edgar Hoover, who to that point was entering his third decade as the first and only FBI Director in U.S. history. Ever since the March on Washington the prior August in 1963, the FBI had been plotting to expand its campaign against King, who Sullivan had identified as “the most dangerous Negro” in America in a memo to Hoover just two days after the March, which was capitalized by King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

By the time Coretta Scott King opened the package on January 5, 1965, the stakes had risen dramatically during the prior sixteen months since Sullivan and Hoover targeted King. Prior to King’s famed address, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States had amounted to regional gains through campaigns like the Bus Boycott in Montgomery in 1955, the Greensboro sit-ins in 1960, and the Birmingham Campaign in May 1963. But after President Kennedy committed to the cause on June 11, 1963 (a story which I detailed back in June), the movement transformed, as King said, from “more than just getting a lunch counter integrated or a department store to take down discriminatory signs” into “an assault on the whole system of segregation.”

However, that fact did not sit well with J. Edgar Hoover, a man who was raised in segregated schools and came to believe in the mythology of the Lost Cause. Hoover was a traditionalist who first gained power as the director of what was then the Bureau of Investigation in 1925, when he was 30 years old. He then became the Director of the nascent FBI in 1935—a post he would hold until his death in 1972. But most of all, Hoover was a man of complications: while he pursued Communists to no end, he claimed that jurisdictional limits impeded the FBI from stopping lynchings in the South—and while he drove the Lavender Scare of the 1950s that essentially criminalized homosexuality, Hoover was almost certainly a deeply, closeted gay man himself. He and Clyde Tolson, who was his number two at the FBI for the entirety of his tenure, were “life partners” who lived together, rode to and from work together, and went on vacation together.

But more than Tolson, Hoover loved the FBI. And after Sullivan’s memo marking King as a danger to the Bureau’s pursuits, he made up his mind to destroy him. Key to Hoover’s campaign was a man named Stanley Levinson, a Jewish New Yorker who had become a top advisor and speechwriter for King. And Levinson, as King later learned, had also given tens of thousands of dollars to the Communist Party of the United States, a small organization at the time with about 4,000 members. However, this was still the near height of the Cold War. And although Levinson was not a practicing Communist and despite the fact that King’s pursuits to expand American freedoms were as patriotic as Apple Pie, Hoover used Levinson’s ties to obtain a wiretap on King on October 7, 1963—a wiretap approved by then Attorney General, Robert F. Kennedy.

Through the end of 1963, which ended in King’s being named TIME’s “Man of the Year” and throughout 1964, the year King won the Nobel Peace Prize, Hoover recorded King in his office and in hotels, in hopes of finding dirt that would humiliate him. And King—much like the Kennedy brothers—was a serial adulterer. Though the tapes referred to in Sullivan’s letter cannot legally be released until 2027, it is almost certain they contain some proof of King’s infidelities.

But in April 1964, King made a strategic mistake: he went after the FBI, calling Hoover’s organization “completely ineffectual in resolving the continued mayhem and brutality inflicted upon the Negro in the deep South.” While it was a fact, it led Hoover to refer to King, publicly, as “the most notorious liar in the country” later that year. By then, the cake had been baked: he immediately demanded Sullivan blackmail King. Still—despite a face-to-face meeting on December 1, 1964, just a week after the package was sent—neither man backed down. And in the public eye, the favorite in the showdown was clear: Hoover had approval ratings in the 80s, while King, despite his accolades, began to wane in favorability as the gains of the Civil Rights movement became tangible.

Despite the threat, King kept up his pursuit, to bend the moral arc of American history toward justice. After helping President Johnson pass the Civil Rights Act in 1964, he helped shepherd the Voting Rights Act into law in 1965. But then his dream became a nightmare, as cities he had tried to heal had erupted into riots and as the Vietnam War continued to spiral out of control, gasoline to the flames of American chaos. On April 4, 1967, he spoke out against the war in force: “If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read ‘Vietnam’,” he lamented. Throughout the following spring and summer, cities would continue to erupt in what became known as “the long, hot summer.”

The next year, in 1968, King turned 39. By then he had lost the public support he once, briefly, enjoyed. His disapproval ratings were now at 75%, as he vowed to lead what he called the Poor People’s Campaign, first in cities around the nation, and then in a large-scale encampment style protest in Washington, D.C. that spring. Meanwhile—on March 4, 1968—the FBI warned in a message about “Black Nationalist Hate Groups” to its field offices that the Bureau must “Prevent the rise of a ‘messiah’ who could unify and electrify the militant black nationalist movement.” King, the letter said, was among its “primary targets” and instructed its agents to act within 30 days.

Exactly 30 days later, on April 3, 1968, Dr. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. woke up at his home at Atlanta, and kissed his wife, Coretta, before he left for the airport at 7AM. “It was an ordinary goodbye,” she would later say. He then boarded a flight for Memphis, where he was set to stage a Poor People’s Campaign protest in response to a sanitation worker’s strike after two workers named Echol Cole and Robert Walker were crushed to death while loading trash into their truck earlier that year. In his prior visit to Memphis a few weeks before, which ended in a riot, the FBI had alerted reporters that King had fled to the white-owned Holiday Inn. Now, as he arrived again in Memphis, the media was made aware that King would stay at the Black-owned Lorraine Motel, a fact that reporters were eager to share with the public, including his exact room: Room 306.

That night, King gave the last speech of his life. He warned, “The nation is sick. Trouble is in the land.” He continued: We've got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn't matter with me now. Because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

The next day, shortly before 6PM on April 4, King stepped out onto the balcony outside Room 306 and leaned on the railing. He looked out at the cracked concrete of the oil-stained parking lot, the empty swimming pool, and the dilapidated boarding house across the way where rooms went for $8.50 a week. He pawed at the menthol cigarettes inside his jacket pocket, which he never smoked in public. Then a single shot rang out from a Remington Gamemaster .30-06 slide-action rifle.

An agent called Hoover, who was at home. “I hope the son of a bitch doesn’t die,” he said. “If he does, they’ll make a martyr out of him.”

Sources:

Beverly Gage. G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century. 2022.

Jonathan Eig. The Life of Martin Luther King. 2023.

Thank you for this history lesson. I was a small child during this time and was unaware of much of this. Shameful that this wasn’t taught in my school when I was a teen.

I was ten. Immigrated with my family from Türkiye. I was stunned to see photos of Dr. King’s entourage pointing in the direction of the shooter. I didn’t understand why he was killed, but for the first in my young life I understood that America was a place of fear and hatred. Then came Bobby Jr. with the horrific photos of the chaos, the men in suits crowded around him as he gasped on the floor with his last thoughts. By the time I was 15 I was fully “woke” and protested the Vietnam War with the words of Nikki Giovanni repeating in my head and “Free Angela” lovingly embroidered on my jeans. My parents surely must have worried how bringing their 4 year-old daughter to the land of “milk and honey” would change the trajectory of her life.