The Happy Warrior from Minnesota had one chance to introduce himself to the country. One chance for a first impression, something most politicians with national ambitions—and they all have national ambitions—never get. His chance would come in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: a state Republicans were desperate to win back from the Democrats, and one of the keys for their plan for victory.

Inside the hall, though, the Happy Warrior—sleepless from days and nights of preparation but still grinning—would hit his mark. It was July 6, 1948. And Hubert Horatio Humphrey, the 37-year-old Mayor of Minneapolis, was set to address the Democratic National Convention.

The 1948 election was a turning point in American electoral history. From 1932 to 1944, Franklin Roosevelt had dominated like a colossus. He had not just won four consecutive terms, he blew out his competitor each time, winning by well over 300 electoral votes in each election—including a 523-8 Electoral College victory in 1940 over the late, great Alf Landon. Roosevelt overcame the Depression and Second World War to put America permanently atop the global order—all without the use of his legs.

But for all that FDR did—and for all the protections New Deal programs like Social Security created—he did it explicitly on the back of Southern Democratic support in the House and Senate. And for the whole of American history, Southern support has come at a cost. And that cost has been paid through the denigration of Black Americans. Black communities were “redlined” so as not to receive adequate relief that white communities received and Black Americans—and Black veterans—were excluded from the benefits of programs like the G.I. Bill, which helped upwardly transform the white American middle class, granting home loans and access to universities that were previously off-limits.

To consider the impact of this bargain, you can think of a white worker and how badly he was impacted by the Great Depression—by a level of poverty so deep and so universal that it was considered inescapable—and then think of how New Deal work programs and new government protections helped him and his family. How the idea of having a stable job, financial security for his family, not to mention the idea of owning a home or even going to college, changed him and his family’s future.

Then, you can think of a Black worker or a Mexican worker—already lower down the food chain in American society—and how his life could have been turned around by those programs and those benefits, but how he was largely shut out. How his children were shut out, and following it logically, how his grandchildren today never received the wealth that may have been created through the opportunities stemming from a college degree that was never given or a home purchased with a loan that was never granted. This was the cost of bigotry—and for FDR, this was the cost of Southern votes to pass the New Deal.

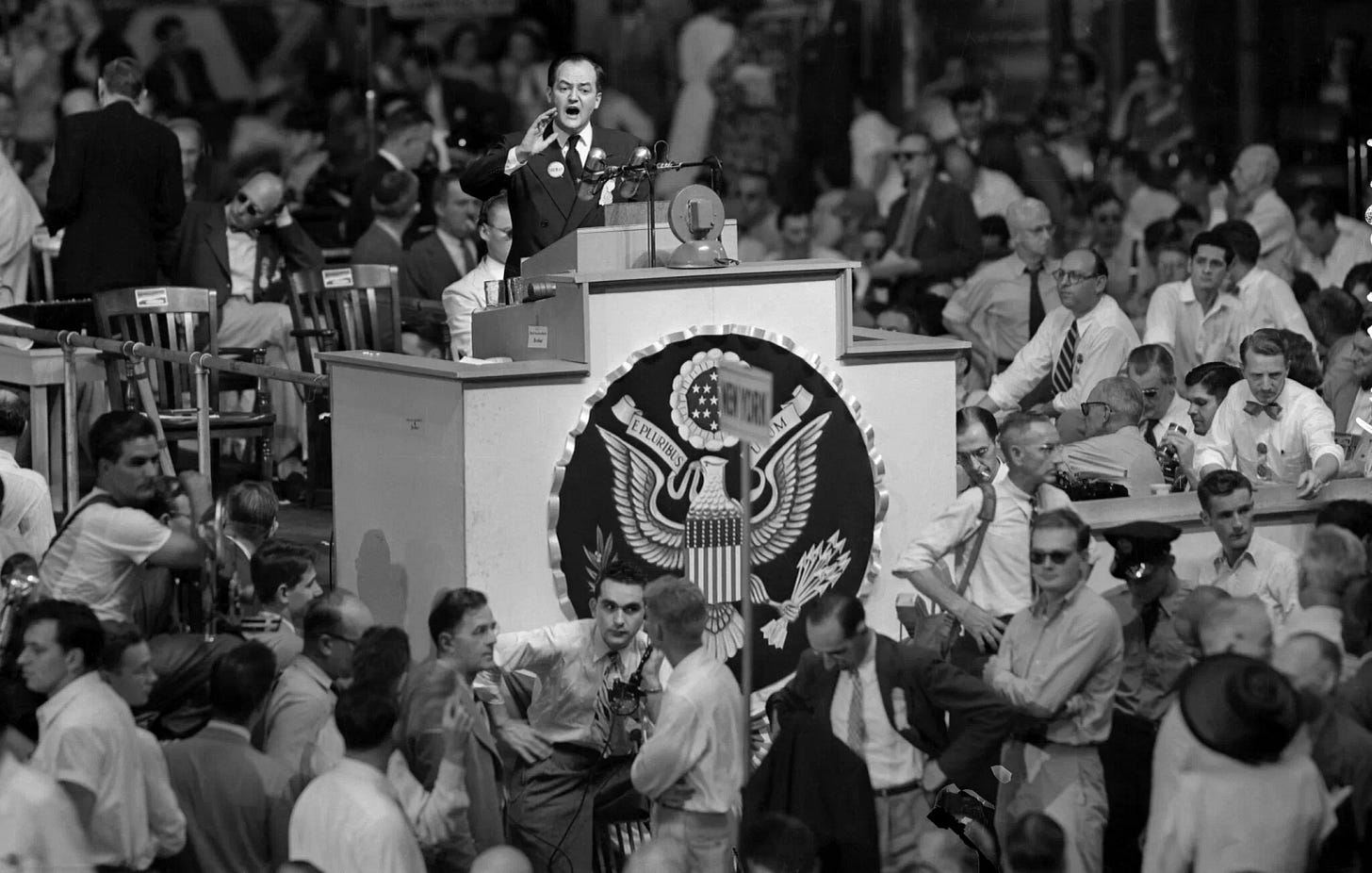

This was all on Hubert Humphrey’s mind when he stepped to the stage inside Philadelphia’s Conventional Hall. It was 93 degrees—the last major party convention that didn’t feature air conditioning. Humphrey’s goal was simple: he wanted the Democratic Party to finally commit itself to Civil Rights—to the idea of equality for all Americans. To do that, he needed to pull off the near-impossible. He had to convince party delegates to vote against the majority’s Civil Rights plank—and vote for a minority plank he and other liberals had crafted. In effect he was asking for the Democratic Party to turn its back on its most dependable stable of support: the South. All that in an election where Democrats needed every possible vote in order to win.

Humphrey had more on the line than most. As Mayor of Minneapolis, he had secured the nation’s first real-deal Fair Employment Practices law. And that fall, he was the Democratic nominee in Minnesota’s U.S. Senate race. But more than a few told him that if he went all the way in his speech—and committed to the minority plank and Civil Rights—that his career would be finished before it began. That he would lose his Senate race, help Republicans win the White House, and sacrifice “a brilliant future for a crackpot crusade.”

All night before his speech, he went back and forth on what to do. Until 5AM, he stayed up with his liberal colleagues in his room inside the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, debating the best path forward until abruptly he said, “I’ll do it,” and ordered them out so he could write his speech right then and there.

That night, the Happy Warrior delivered a speech that many in the audience remembered as the best they ever heard. He addressed the crowd of white faces—many of whom had no idea who he was—“to those who say that we are rushing this issue of civil rights, I say to them we are one hundred and seventy two years late.”

He continued, “To those who say that this civil-rights program is an infringement on states’ rights, I say this—the time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states’ rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.”

Later that night, the Civil Rights plank vote was held among the delegates—the minority plank, Humphrey’s plank—passed 651 ½ to 582 ½. For the first time, Black voters in northern states and cities would embrace a Democratic Party that championed Civil Rights.

There was fear that Humphrey’s speech—and the party plank he pushed to passage—would cause a walkout among Southern delegates. Those fears were well-founded. As the official roll call for the presidential nomination began, delegates from four solidly Democratic states walked out: Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and South Carolina. Those states would form their own party—the States’ Rights Party—and nominated South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond to be its nominee. Come November, Thurmond would win all four states and their 39 electoral votes. It was the first time since 1872 that all four had voted for a party other than the Democrats.

Humphrey sailed to election to the Senate—and President Truman, against all projections, beat Governor Thomas Dewey to win the 1948 election. Within 16 years’ time, in 1964, the same states that walked out in 1948 would be among the only to vote for Senator Barry Goldwater against President Lyndon Johnson, who promised to pass a Civil Rights Bill—one that finally embraced the sunshine of human rights. That year, Johnson’s running mate was Hubert Horatio Humphrey—the Happy Warrior.

Sources:

Caro, Robert. Master of the Senate. 2001.