The room smelled of death.

And because the house wouldn’t get electricity until 1891, it was dark. The oil lamps from the three chandeliers overhead provided the only light. There were 24 chairs in the room then that had been purchased in 1824, now weathered and worn, and a single ragged carpet. The drapes were crimson with gold fringe, and gold tassels and the wallpaper was crimson too—all appearing darker because of the low light. The room—the East Room of the White House—had seen the highs and lows of the previous four years.

In April 1861, about 60 soldiers from Kansas used it as a temporary camp before further barracks could be built in Washington, D.C. The month prior, Abraham Lincoln had been inaugurated as president on March 4. He was the first Republican president in American history, the standard-bearer for a party that appeared in its first national election only four years prior. The party was founded on the principle of abolition, and the idea that the United States could not exist half slave and half free. Lincoln had previously been a Whig and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois’ 7th district in 1846—before losing his seat in the next election. In 1858, he ran against Stephen A. Douglas for the Senate, a race he also lost. By November 1860, he was President-Elect of a nation that was splitting in two.

That Christmas Eve, South Carolina seceded from the Union, soon followed by ten other Southern states, in an attempt to create a new nation, called the Confederate States of America. Alexander Stephens—a former Georgia Congressman and the Vice President of the Confederate States of America—would best summarize the project of the Confederacy just weeks after President Lincoln’s inauguration: “its cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.” There was no talk of state’s rights or accusations of northern aggression—just the maintenance of a racialized economic order built on the ownership of other human beings.

Over the next four years, Lincoln would free four million Black slaves in the South and 750,000 Americans would die fighting one another. On March 9, 1864, after the war had turned in the Union’s favor, President Lincoln used the East Room to host a reception for the man he was promoting to Commanding General of the U.S. Army, Ulysses S. Grant. Grant, despite his West Point education and combat experience in the Mexican American War, began the war as a 38-year-old volunteer. After stirring victories at Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga, Lincoln said of Grant, “I can’t spare this man.” And it was there—in the East Room—where the two men met for the very first time.

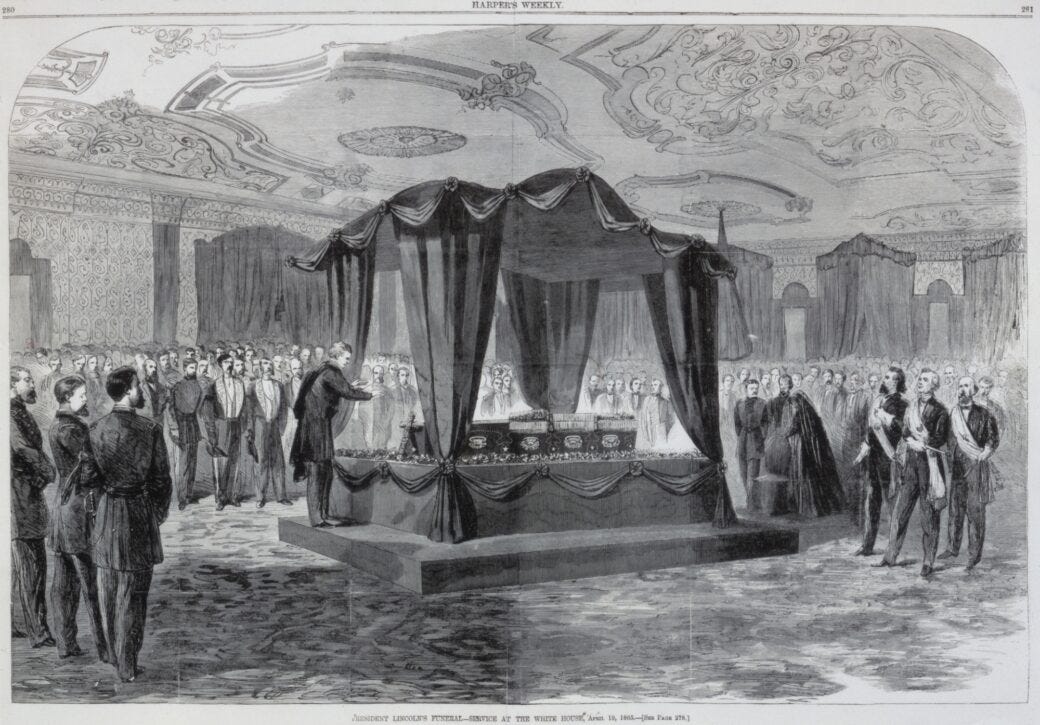

Thirteen months later, on April 9, 1865, Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Grant, ending a Civil War that would continue to echo in impact for the remainder of American history. Six days later, President Lincoln was assassinated. His body would lay in state for days in the East Room, where his funeral was held on April 19. 600 mourners filled the East Room, so many people that they overflowed into the Green Room. Thousands more hung beyond the White House fence, hoping for a glimpse at the casket of their fallen hero. Inside the room, at the head of catafalque, alone in full uniform, sat General Grant. Mary Todd Lincoln—who had also held a funeral for her son, Willy Lincoln, in the East Room in 1862—could not even bear to enter.

As the funeral ended, a black drape was placed over Lincoln’s coffin, as it was placed in a carriage led by six white horses, on the way to the Capitol rotunda to lay in state. It would be the exact same processional followed nearly a century later when John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963. First his death in the limousine on Elm Street in Dallas, then Parkland Memorial Hospital, then Air Force One, and then—the East Room. In fact, of the eight presidents who died in office, all but one—James A. Garfield—laid in repose in that room. It was in that room where men who had reached the highest office their country had to offer here on Earth, crossed over into the Great Unknown.

But the East Room was more than a funeral parlor. Nellie Grant, Alice Roosevelt, Jessie Wilson, and Lynda Bird Johnson were all married in that room, each walked down the aisle by their father, the President. President Nixon gave his final farewell address to his staff in the East Room at 9 AM on August 9, 1974. He cried uncontrollably at times, and told the staff and the cameras, “Nobody will ever write a book, probably, about my mother. Well, I guess all of you would say this about your mother…my mother was a saint.” Thirty-seven years later, President Obama announced the death of Osama Bin Laden in that room.

And in that room—that room where American history had played out across the centuries in a space measuring just 2,884 square feet—the 2024 presidential election began when President Donald Trump decided to declare himself the winner of an election he had lost just after 2:30 AM early on Wednesday morning on November 4, 2020. Looking out on a crowd that included his staff and his family, he stumbled through nerves to say that “as far as I’m concerned, we already have won.”

He understood the power of his lie—a lie which still propels him today—but didn’t understand the history that surrounded him in that room. Today, he stands to reinherit that room, forever ambivalent to the words of a man that once laid in state there.

“We are not enemies, but friends,” Lincoln said at the end of his first Inaugural Address. “We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

God willing, we will heed those words today and in the weeks ahead.

Sources:

James McPherson. Battle Cry of Freedom.

https://www.whitehousehistory.org/abraham-lincoln-funeral

https://clintonwhitehouse3.archives.gov/WH/glimpse/tour/html/east.html

https://www.history.com/news/abraham-lincoln-ulysses-s-grant-partnership-civil-war

Amazing writing--thank you so much