The Great Debate

Millions of Americans—those who cared to tune in, anyway—were gathered in front of the television to watch a presidential debate, unsure of the direction of their country, unsure of the candidates’ grip on reality, and completely unsure, after decades of misguided change, about what came next.

The year was 1992.

By 1992, the ideological waters in America had seemed to stagnate. Less than 30% of the country said it was paying attention to national politics at all.[1] Vietnam, Watergate, dithering wages, rising inequality, increasing crime—it seemed as though the good times were really over for good. Beginning in 1968, Republicans won the White House in five out of six elections, the only outlier being the Carter presidency, which with its sky-high corporate profits, record military budgets, and decreased social spending, looked very much like a continuation rather than an outlier.[2]

Merrily, merrily, America rowed its boat rightward down the stream.

An aura of discontent and disillusion seemed to permeate the nation. President George H.W. Bush, it seemed, was a far less charismatic Reagan Lite. A recession began in 1991 as unemployment reached 7.8%,[3] nearly halving his approval rating which had reached 89% in the wake of the swift victory in the Gulf War. Along with the sputtering economy, Bush had to deal with a violent crime rate that had reached an all-time high, especially in predominantly Black center cities where the spigot of social spending had turned off long ago in favor of increased policing and incarceration, creating a vacuum of joblessness and poverty as White Flight took hold in suburbs across America.[4]

The United States suddenly stood alone, and it seemed, unsure on the world stage. The Cold War had officially ended just months prior and for the first time since the outbreak of WWII, Americans lacked a common enemy. In a post New Deal, post Great Society America—movements that defined the United States’ strides towards racial equality and its creation of the most powerful middle class in history—Americans were becoming less equal, not more.

The prior 12 years had amounted to an upward redistribution of wealth. President Reagan had cut the top bracket’s income tax from 70% to 28%.[5] The minimum wage, which was in line with the poverty rate in 1980 at $3.35 per hour, had fallen 30% below the poverty rate by 1990, at $3.80 per hour.[6] Reagan had also cut the corporate tax rate and heavily influenced the movement of industry away from the unionized northeast and Midwest, toward the unregulated South and West.[7] And George H.W. Bush, perhaps the most well-qualified man ever to hold the office—a Navy pilot in WWII shot down in battle, a Congressman, Ambassador to the United Nations, Ambassador to China, Director of the CIA, and a two term Vice President—simply followed the policies he once called “voodoo economics” set forth by his predecessor. That which had made America great had been gutted. A new gilded age had begun.

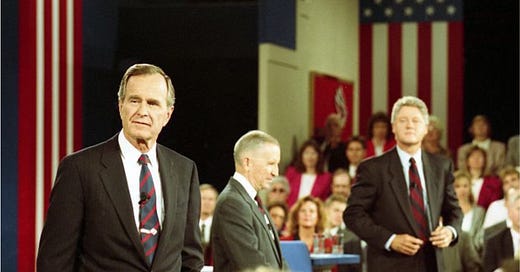

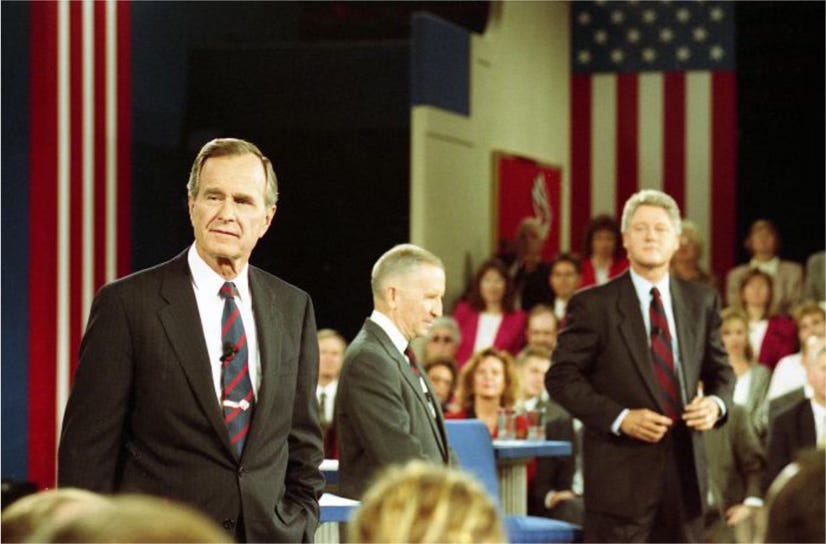

This was the backdrop to the 1992 debates—three in total—all held within a few days of each other in October. That year, for the first and to date only time in American history—a crystallization of the discontent—there were three candidates on stage. There was the Texas billionaire, Ross Perot, an anti-trade populist and uniquely cartoonish figure who pronounced schools as “skooz” and appeared to be about as tall as a bar stool. There was Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton, a new kind of slick politician, so covered in slime that he almost glowed. And there was President George H.W Bush, who could’ve been president in 1892 and would not have been out of place, and who went through the motions of the debates like he was chairing an Elks Club meeting.

Throughout the first debate, Bush boo-hooed what he called “pessimism” from Clinton and Perot. He promised that after he was reelected alongside a new Congress that “gridlock will be gone.” But what President Bush didn’t realize was that the details he spouted, the accomplishments he championed, the statistics he memorized from a notecard likely written by an Ivy League educated aide, did not matter to the public anymore. This was 1992—the top grossing movie was Batman Returns, a sequel; the second was Lethal Weapon 3; the fourth was Home Alone 2; and the third and fifth highest grossing films, Sister Act and Wayne’s World would both have their own sequels the very next year.[8] America’s attention span had shrunk as had the expectations of its government; it now wanted popcorn, air conditioning, and a 64 ounce Diet Dr. Pepper—not a lecture about interest rates.

America wanted star power in the Oval Office and it had suddenly realized four years too late that Bush was the understudy who had stumbled into the role. The time for recasting had come—and about halfway through the second debate it found its new leading man.

In an open, in the round, town hall style forum without podiums, a young Black woman stood up to ask a question about how the national debt had personally impacted the three candidates, and if it hadn’t, how they were fit to lead. As she started to ask the question, George H.W. Bush raised his right wrist to his eye level and checked his watch, learning that it was 9:45PM inside the Richmond auditorium.

As the seconds ticked away on the debate and the Bush presidency, the young, undecided voter finished her question, asking how the next president might solve “the economic problems of the common people if you have no experience in what’s ailing them.” After an awkward pause, Perot went first, offering an answer about how he had sacrificed a great life in pursuit of public service, a kind of canned and clipped answer not typical of Ross Perot. Next was President Bush, launching into a stumbling, awkward answer about, “Well, I’m sure it has, I love my grandchildren, I want to think that they’ll be able to afford an education.” Bush—who had gone to Yale, whose father had gone to Yale, whose son had gone Yale and also later became president—then stumbled again. He asked, “are you suggesting if someone has means then the national debt doesn’t affect them?” The way he said “means” alone suggested a country club membership. The woman answered, “I’ve had friends that have been laid off from jobs, people who cannot afford to pay the mortgage on their homes, their car payment, I have personal problems with the national debt.”

The moderator, ABC’s Carole Simpson, stepped in as the camera held on the President’s bewildered face, his mouth slightly open. He then gave another canned, meandering answer: how she, the undecided voter, should spend a day in the White House and hear what he hears, how he had seen a bulletin in a Black church a few weeks ago warning about teenage pregnancies, how “you have to care,” how “everything comes out your pocket and my pocket,” finally hitting her with the heartfelt zinger: “of course you feel it when you’re President of the United States—that’s why I’m trying to do something about it by stimulating the export, investing more, better education system.” As he thanked her for her question, Jeb Bush’s father might as well have said, “Please clap.”

Finally, it was Governor Clinton’s turn. As he stood up and walked toward her—the other two candidates had stood in place for their answers—he looked like a shark torpedoing its way to the scent of blood. Instead of launching into policy, Clinton started by engaging directly. “Tell me how it’s affected you again…You know people who’ve lost their jobs and lost their homes?” he asked, moving closer, as the woman nodded. Clinton sensed the moment. He sensed the frustration. He sensed that in this woman—and so many Americans like her—a deep anxiety about the future and whether her voice mattered at all as to its outcome. Clinton—standing at Six Foot Two, a Rhodes scholar with thick salt and pepper hair and Southern accent—looked directly into the woman’s eyes, never removing his gaze. He was just a few feet away now. He continued, “in my state, when people lose their jobs there’s a good chance I’ll know them by their names, when a factory closes, I know the people who ran it, when the businesses go bankrupt, I know them.”

He went on, charging that “the national debt is not the only cause of that. It’s because America has not invested in its people, it is because we have not grown, it is because we’ve had 12 years of trickle-down economics…Most people are working harder for less money than they were 10 years ago…It is because we are in the grips of a failed economic theory.” As Governor Clinton finished, the camera cut back to President Bush—his mouth literally agape—as if his school record in the 100 meter dash had just been obliterated by some kid who didn’t even warm up.

Clinton won the debate and the election because he portrayed empathy and understanding—something Bush seemed incapable of even conceptualizing. So often that is what presidential debates are about: who seems to understand the anxieties of Americans. Facts and figures often only matter if a candidate stumbles when reciting them. In a post-Watergate world, Americans understand the President is not an arbiter of truth but a representation, a fallible television character that is given leeway to lie but not to bore.

This Thursday, America will again have a presidential debate. And despite the upheavals and profound changes since 1992, the country today is still seemingly in search of itself—still ridden by economic anxiety and comic book movie remakes, and still prone to choosing presidents based on presentation rather than policy. What happens in the debate, or the election, is anyone’s guess. But what is remembered—by headlines and voters alike—will almost certainly be made in an instant, where one candidate is able to portray a veneer of understanding about that which ails his country. Whether or not that candidate does, sadly, has long been beside the point.

[1] https://news.gallup.com/poll/513128/attention-political-news-slips-back-typical-levels.aspx

[2] Manning Marable. Race, Reform, and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction and Beyond in Black America, 1945-2006. (Oxford: University of Mississippi Press, 2007), 141.

[3]https://www.forbes.com/forbes/2010/0329/opinions-rich-karlgaard-great-recession-digital-rules.html#:~:text=The%201990%2D91%20recession%20in,have%20had%20this%20last%20time.

[4] https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Crime%20Trends%201990-2016.pdf

[5] Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism.

[6] Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism.

[7] Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism, 26.

[8] https://www.boxofficemojo.com/year/1992/?grossesOption=calendarGrosses