There are 365 steps leading up to the United States Capitol.

Thousands of elected officials have walked those steps, the steps that lead to the hallowed halls of American political power. Work on the Capitol began shortly after the passage of the Residence Act in 1790, which moved the national capital from Philadelphia to a new city called Washington, along the Potomac River—which straddled the North and the South. The Act made clear that the new city be inaugurated in 1800 after a decade of building.

But in this new land, there was no infrastructure or labor force. There was nothing but swamp and forest. So, Black slaves—some who had ancestors come to America over a century prior—were brought in shackles from nearby Virginia and Maryland to do the work. Slaves cleared the surrounding forests, slaves laid the foundation of the Capitol building, slaves brought the hulking sandstone up the Potomac River, and slaves worked six days a week—in sweltering sun and freezing cold alike—from sun up until sun down. Not one of them was paid. After the Capitol building was partially burned in the War of 1812, slaves helped rebuild it.

Slaves had built and rebuilt those steps again and again.

In the decades to come, slavery would become more important to the United States as the Union grew, the engine that not only powered the South but much of the national economy. Crops like sugar, rice, and tobacco dominated and grew the American economy into a global behemoth—and grew its reliance upon slavery. None more so than cotton. In 1800, when Washington became the capital city, the U.S. produced 79,000 bales of cotton—by 1860, it produced five million bales, clothing the Western world.

Eventually, the threat of slavery’s abolition became too much for the American South, whose loyalties laid with their region’s profits, not the country itself. Alexander Stephens—a former Georgia Congressman and the Vice President of the Confederate States of America—would best summarize the project of the Confederacy just weeks after President Lincoln’s inauguration: “its cornerstone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.” There was no talk of state’s rights or accusations of northern aggression—just the maintenance of a racialized economic order built on the ownership of other human beings.

Prior to the ensuing Civil War—a war that killed 750,000—as the nation itself sought to rebuild its very foundations, the Capitol too was rebuilt. By 1850, it had become clear that the United States continued expansion—and the entry of states both slave and free—required a larger Congressional building than originally planned. So, expansion began—including the construction of a larger dome to the Capitol building.

But then the war came. All construction stopped, as the United States Capitol literally sat unfinished—a perfect portrait of a house divided—until 1862 when it was ordered to continue, this time by freedmen and white laborers, as the war went on.

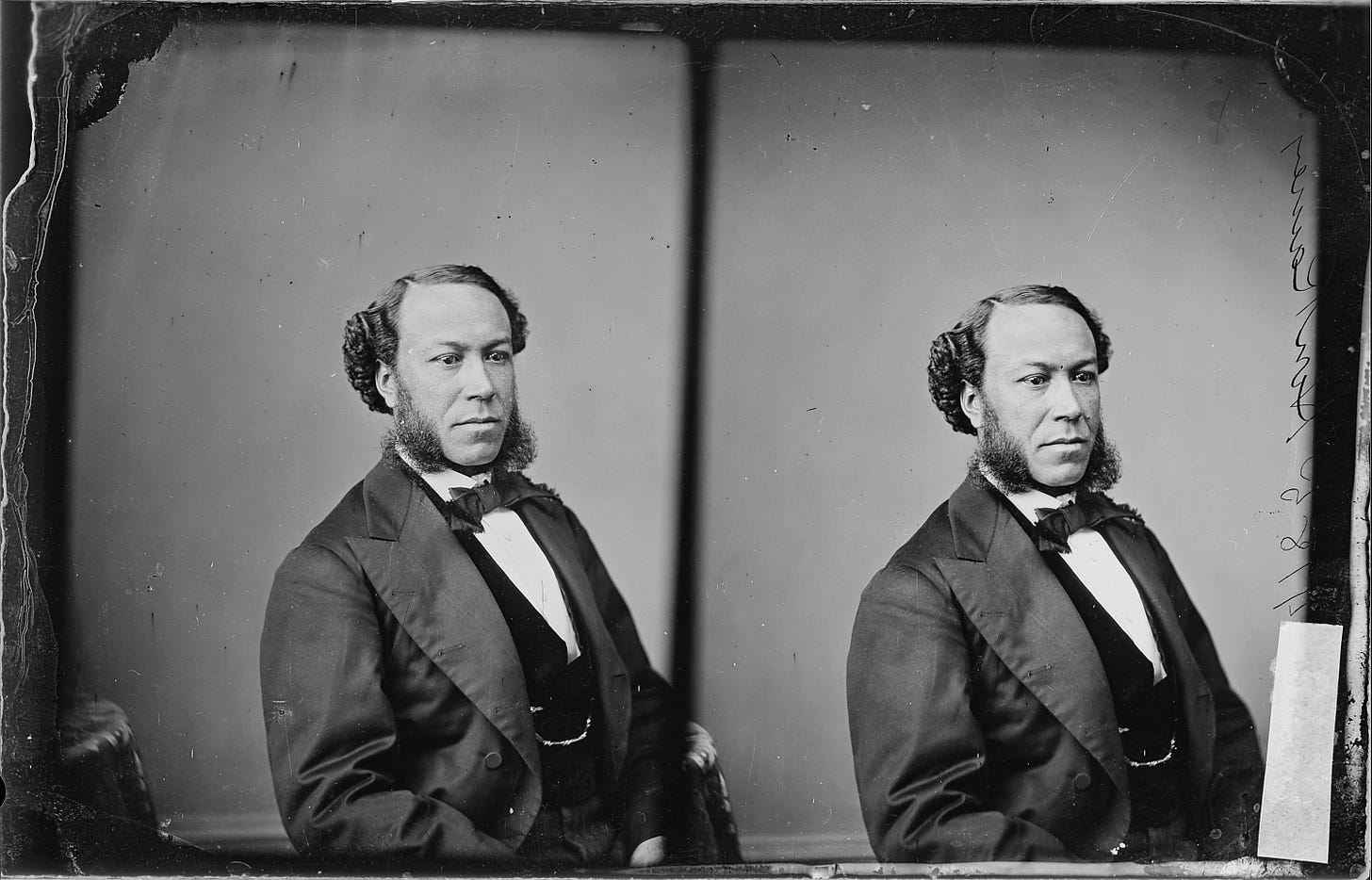

But still those 365 steps remained—the steps that led to great halls and hearing rooms in which the decisions of war, peace, and prosperity were made—and still a slave had never climbed them and gained entry into the seat of power. That is, until Joseph Rainey climbed them on December 12, 1870.

Joseph Rainey was the first Black American to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives, representing the First District of South Carolina, the state that had been the first to secede from the Union. Rainey had not been the first Black man to serve in Congress—that distinction belonged to Hiram Revels, who had become a U.S. Senator from Mississippi earlier that year beginning on February 25.

However, Revels was elected to his seat by the Mississippi state legislature—as were all Senators elected by their legislatures until the passage of the 17th Amendment in 1913—and Revels sat barely a year, leaving the chamber on March 3, 1871. Rainey, however, had been elected directly by the people of his district, people whom for the very first time after the passage of the 15th Amendment in February 1870, included Black voters.

And also, unlike Revels, Joseph Hayne Rainey had been born a slave.

In 1832, as the Union continued to grow, Rainey was born in Georgetown, South Carolina. When Rainey was a child, his father gained employment as a barber and purchased his own freedom and the freedom of his children. However, freedom did not mean the right to vote, or even the freedom to learn how to read or write. Like his father, Joseph became a barber too. When the war came, Joseph was conscripted by the Confederacy and forced to be a cook and laborer. In 1862, he saw a way out: an escape eastward to the island of Bermuda. For four years, Joseph and his family lived peacefully in Bermuda, finally returning to Charleston in 1866. He used what money he had to make inroads in the growing Republican Party, and in a city that was nearly half Black, he made an impression. He won a seat in the State Senate; soon, a special election was held for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. With federal officials overseeing the election and allowing Black citizens to vote, Rainey won.

In total, during the Reconstruction era, sixteen Black men served in Congress—nine of them had been born into slavery. Alongside Revels, Bruce Blanche was elected to the Senate from Mississippi—the only former slave ever to sit in the Chamber. Others like Benjamin Turner of Alabama who served in the House from 1871 to 1873 and Josiah Walls of Florida, who served in the House from 1871 to 1876, were both slaves during the war itself, only earning their freedom upon the Union’s victory.

When these men sat for their seats—and they were all men—some argued that the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, which ruled that Black Americans were not citizens and therefore the Constitution did not apply to them, was still in effect. Others, relenting the reality of the Reconstruction Amendments argued that Revels and others could not be seated because the Constitution requires that a Senator need have been a citizen for nine years prior to taking office—and that only two years had passed since the ratification of the 14thAmendment that granted Black citizenship.

But as Charles Sumner, the ardent abolitionist and perhaps the greatest of all the hallowed Massachusetts Senators to serve in American history, said "the time has passed for argument. Nothing more need be said. For a long time, it has been clear that colored persons must be senators."

But the promises of victory and the promises of Reconstruction were soon broken.

On Christmas Day 1868, President Andrew Johnson—the Southern Democrat that succeeded Lincoln—issued a blanket pardon for all former Confederates. The trial of Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy’s president, never took place. Alexander Stephens himself reentered Congress in 1873, serving alongside former slaves. The traitors, slave owners and insurrectionists weren’t just allowed to live freely, they were given back power.

After 1877, white Southerners—“redeemers” they called themselves—sought to overturn the principles of equality that had, they felt, been forced upon them. Their way of life was one of dominion and with the specter of federal intervention gone, they restored what they believed to be the “natural and normal condition,” as Alexander Stephens laid out.

Reconstruction officially ended in the South after a tumultuous and corrupt 1876 presidential election led to an undecided outcome between the Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and the Democrat, Samuel Tilden. The election had been marred by political violence across the South, as “rifle clubs”, like the “Red Shirts” in Mississippi and the Carolinas, and the “White League” in Louisiana, operated as paramilitary organizations to intimidate and kill would-be Republican voters, Black and white alike, to help the redemptionist Democratic Party. As one South Carolinian said, the idea was for each Democrat to “control the vote of at least one negro by intimidation,” and to understand that “argument has no effect on them: they can only be influenced by their fears.”

Eventually, behind closed doors, a bipartisan Electoral Commission in Washington made up of Congressmen, Senators, and Supreme Court Justices agreed that Hayes, the Republican who was more pro-business than pro-Reconstruction, was to be the winner and next president—and as a compromise, federal troops would leave the now “Solid South” altogether. If the Civil War, and subsequently the project of Reconstruction, was a battle to restore and uphold democracy in the Southern United States, the South had won.

Joseph Rainey walked down the steps of the Capitol one last time on March 3, 1879, only to be replaced by John S. Richardson, a former captain in the Confederate Army. One by one, the Black Americans who had represented the height of victory for the Union—of the ultimate symbol of American democracy’s triumph—walked down those steps, many without so much as the right to vote any longer.

The last Black elected official during the period, George Henry White, a North Carolina congressman, left office in 1901 because the state had changed its constitution to disenfranchise Black voters. In what would have been his last election, White could not even vote for himself. North Carolina Democrats—many of whom had led a coup that killed hundreds of Black citizens in Wilmington, North Carolina—celebrated. One wrote, “from this hour on no negro will again disgrace the old State in the council of chambers of the nation. For these mercies, thank God.”

For the purposes of their lifetimes, they were right—the next Black elected official from the entire South waselected in 1972, when Barbara Jordan was elected to the House from Texas’ 18th district. After Revels and Blanche there has never been another Black U.S. Senator from Mississippi—and only 12 Black Senators in United States history.

After Joseph Rainey’s departure, the last Black American to represent South Carolina during the period was George W. Murray, who served until 1895 when he too was forced out of office. After Murray, South Carolina’s next Black representative would not be elected for nearly a century, until 1992—when Jim Clyburn was elected.

He still serves in the House today, walking the 365 steps up in the Capitol, into the halls of American power.

Sources:

W.E.B. DuBois, Black Reconstruction, 1935.

Rayford Logan, The Betrayal of the Negro, 1954.

Eric Foner, Reconstruction, 1988.

Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, 2006.

I honestly learned a lot reading this

365 steps full with history!