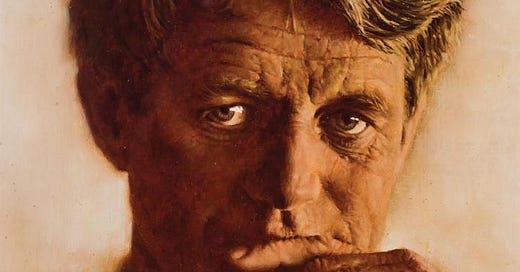

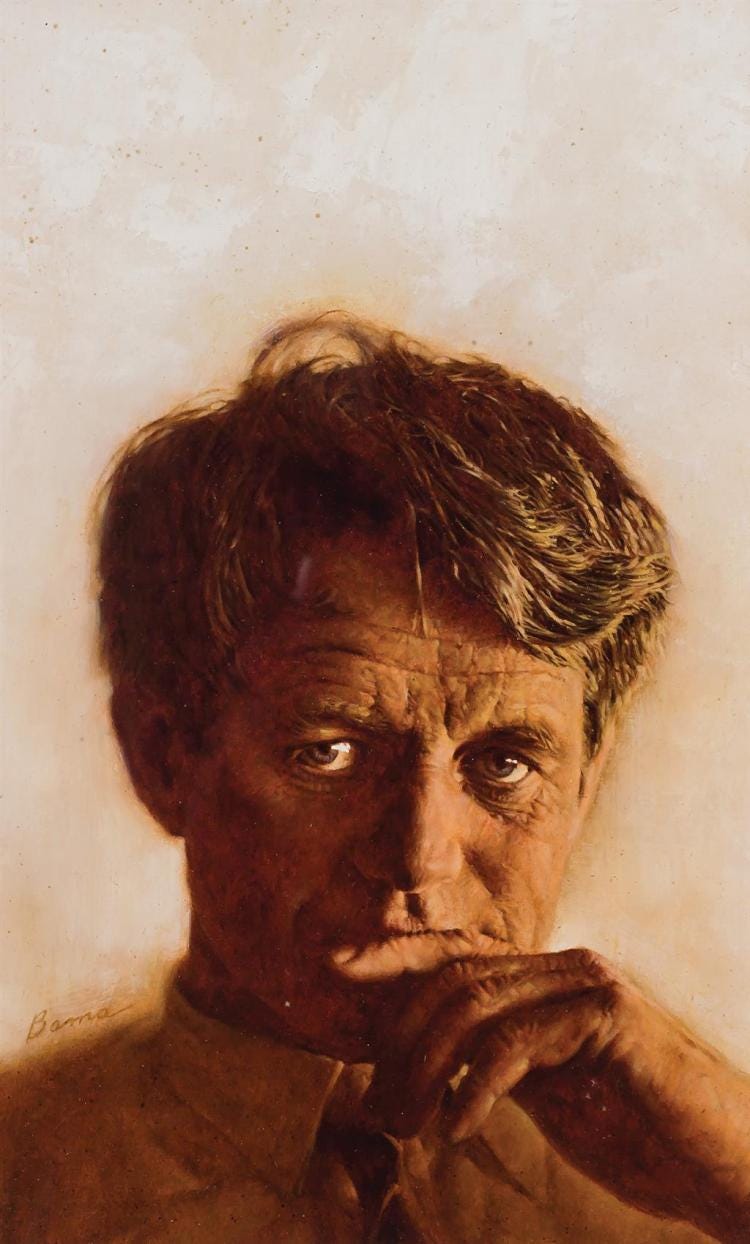

There were two Bobby Kennedys.

The one history remembers—who sought to continue the causes of his slain brother, who sought to send out ripples of hope into the world, and whose own life ended in tragedy. But before his brother Jack’s death, there was another Bobby: ruthless, raging, and often blind to reality.

The finest moment of Robert F. Kennedy’s public life, the version that’s often recounted, happened on the back on flatbed truck. It was a spring night in Indianapolis, Indiana—a night in which the flames of American hatred rose still higher—for the prince of peace, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., had been shot and killed outside the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Kennedy, for his part, had been campaigning for the Democratic nomination for president in 1968, and the upcoming Indiana primary.

Kennedy had been in the race for just over two weeks, announcing his candidacy on March 16, as it became clearer that Democratic voters wanted to move away from President Lyndon Johnson—who had won in the largest landslide in American history in 1964—as the lies that had escalated an already unpopular and unwinnable war in Vietnam spilled out into the open. In the first nominating contest of the year, the New Hampshire primary on March 12, Johnson had nearly lost to a surprise challenger, Senator Eugene McCarthy. Four days later, Robert F. Kennedy—New York’s junior Senator, the former Attorney General of the United States, and the brother of the slain President—was in. Then, on the evening of March 31, President Johnson announced he would no longer seek a second term.

A few days later, King was dead. After campaigning in South Bend and Muncie, Bobby Kennedy heard the news about King before boarding a flight to Indianapolis. Instead of cancelling his rally scheduled in a heavily Black neighborhood, Bobby pressed on—and broke the news to the crowd. As he did so, many in the crowd audibly wailed. He had no podium, no teleprompter, just a microphone and a crowd in need of consoling, and potentially—as in many other cities that night—on the verge of rioting.

But he met their anger with understanding. “For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States, we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times.”

He continued, “We can do well in this country. We will have difficult times; we've had difficult times in the past; we will have difficult times in the future. It is not the end of violence; it is not the end of lawlessness; it is not the end of disorder.” Finally, he concluded, “Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world. Let us dedicate ourselves to that and say a prayer for our country and for our people.”

There were no riots in Indianapolis that night.

Tragically, Bobby Kennedy himself would be killed by an assassin’s bullet just two months later on June 6, 1968 while he cut through the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles—just after winning the California primary.

But there was another Bobby Kennedy. One whose instinct was not always to make gentle the life in this world. Early in his life, Bobby was driven by many things—personal ambition, patriotism, and the expectations of his family. But perhaps most powerful was anger.

The seventh of Joseph and Rose Kennedy’s nine children, Bobby never forgot what had happened to his father. In the 1930s, Joseph Kennedy had made a fortune, becoming one of America’s richest men and one of the Democratic Party’s largest boosters. In exchange, he was rewarded by becoming the first Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, and more notably, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom in 1938—and if things went to plan, Joseph Kennedy hoped to be the Democratic nominee in 1940. However, as the Second World War broke out the next year, Joseph Kennedy revealed his true character to be less than a profile in courage.

When the first bombings of London were threatened, Ambassador Kennedy moved the family and himself out to the countryside. He told one reporter, “Democracy is finished in England. It may be here [in the United States].” In the press, Ambassador Kennedy wasn’t just openly anti-democratic, but also openly antisemitic. Eventually, Roosevelt recalled his appointment in 1940.

Years later, as his son Jack climbed the political ladder, this episode was still well known. In the lead up to the 1960 Democratic primaries, Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson had called Joseph Kennedy “a Chamberlain umbrella man,” referencing Ambassador Kennedy’s advice to follow Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and appease Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany—an attitude shared by other ultrarich Americans who thought shutting out one of the world’s largest economies and entering a world war would be bad for business, just as it had been during WWI.

This ate away at Bobby when his brother Jack settled on Lyndon Johnson as his running mate. Bobby seethed in anger and tried to convince Jack to choose someone else until the last possible moment in the lead up to the choice of his running mate in 1960. Instead of seeing the political advantage of having Johnson, Bobby saw red.

Bobby couldn’t let it go. In many ways, he was his father’s son. As Ambassador Kennedy would say: “Bobby hates like me.” When Bobby was introduced to Johnson in the Senate cafeteria years earlier—when Johnson was Senate Majority Leader—Bobby didn’t stand like the others to shake his hand. He seethed and stared. When Bobby was Attorney General and Johnson the Vice President, Bobby conceived of every possible maneuver to make it clear that he was the second most important man in Washington, not the Vice President.

But Bobby’s anger had by then long been established. He had been a lawyer for Senator Joseph McCarthy’s red-baiting Senate committee in 1953. But unlike many who used the threat of Communism as a useful political tool—including McCarthy himself—Bobby seemed to take the threat personally. He gained the reputation as a hot-headed hard charger, hunting down Communists as a kind of personal crusade. By 1957, he had turned his focus to the Teamsters Union and Jimmy Hoffa, still viewing the world in absolutes. But to him, Hoffa wasn’t an outlaw, he was an enemy of Bobby Kennedy. Instead of clerically pursuing him as others later did, Bobby made it personal and failed to convict Hoffa.

Then, after his brother’s election to the presidency, Bobby was appointed to be Attorney General of the United States at just 35 years old, where Bobby found a new enemy: Fidel Castro. And like all his enemies, he did not want to weaken them, but destroy them. After the embarrassing episode at the Bay of Pigs in the early days of the administration, Bobby personally took over covert “Operation Mongoose” to kill the Cuban dictator. Then, as the tenuous relationship grew into an international incident—during the 13 days of the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962—it was Bobby Kennedy, the last man in the room, who urged his brother to bomb Cuba in order to kill Castro, and threaten humanity itself in the process. If Nuclear War was the cost of a vendetta, so be it. Bobby would get his man in the process.

And then came the reality of his relationship with Dr. King, the man he eulogized so elegantly in Indianapolis. For years, the man who ran the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, had pursued King. Hoover was a racist, plain and simple, who viewed King’s crusade for racial equality as harmful to the version of America he sought to protect. Hoover believed that King was under the influence of Communists, and perhaps a Communist himself. Eventually, Hoover found a seam: Stanley Levinson. Levinson, an advisor and speechwriter for King, had been associated with the Communist Party in the early 1950s, long before he met King. After finding the link, he asked the Attorney General—Robert F. Kennedy—to approve wiretaps on King. He did so.

For the next five years, the FBI used those wiretaps to try and destroy King’s life, including sending forged letters about King’s marital affairs that they hoped would lead King to kill himself. But King was no Communist—he was an American patriot of the highest order, whose only goal was to improve the country he loved.

But before his brother’s death—before something inside him turned toward the light of peace and understanding and away from the hatred of outlaw justice—Bobby Kennedy was prone to conspiracies from men like McCarthy and Hoover and the kind of bull-headed thinking that has long sought to prevent progress in the United States, thinking that is still alive and well.

There were two Bobby Kennedys. Sadly today, in 2024, there’s just the one.

You make me wonder if we’d have been better off or worse if Bobby was able to run and won ….