It was early evening during that strange interregnum after Christmas and the houseguest needed a drink. For over a week by then, he had tormented his host just by the hours he kept: not appearing until mid-morning at the earliest on most days, and without fail, staying up until 3 AM most nights.

While others in the house were settling into that day’s work, the houseguest would be just getting up—ripping off his black satin sleep mask and lighting a cigar. As one future biographer wrote, “He, not the sun, determines when he will greet the new day.” The houseguest would then eat his breakfast alone, as he did most days of his life, often wolfing down leftovers from the previous night’s dinner, sometimes with a glass of white wine or Pol Roger champagne, but most often, with a glass of Johnnie Walker scotch and soda that he would make last through most of the morning. While he was often drinking, he was rarely ever drunk.

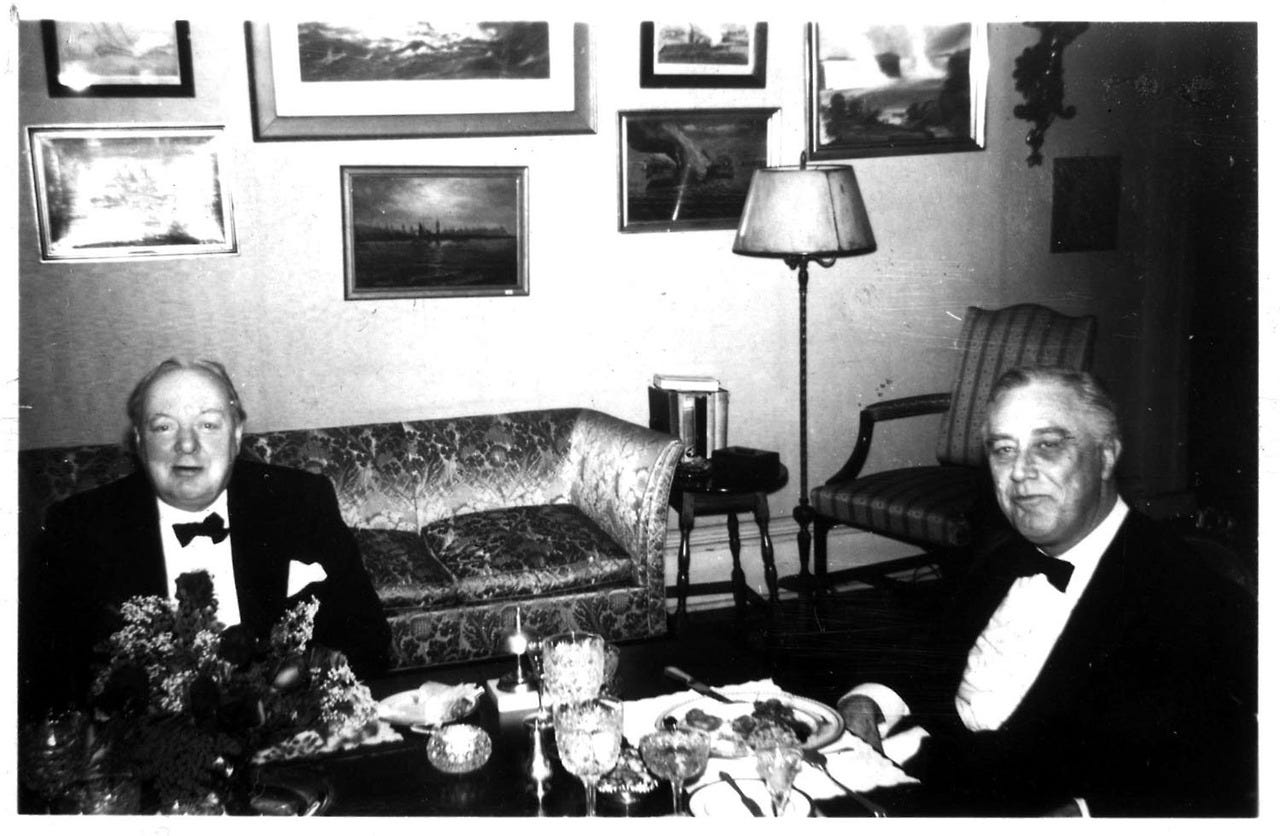

That particular day, his host didn’t see him until just before dinner. “Evening, Mr. President,” the houseguest called out upon entering the room. Despite his unremarkable appearance, the 5’7” cherubic figure with a pink, ruddy face and ice blue eyes made an immediate impression on anyone he encountered.

“Have a good nap, Winston?” the President asked to a grumble.

“Will you have one of these, Winston?” the President asked, gesturing to the tray of drinks he had fixed in front of him.

“What are they?” the houseguest asked.

“Orange Blossoms,” replied the President with a smile, offering the cocktail that became a hit in the 1930s, made up of gin, sweet vermouth, and orange juice. The houseguest—Prime Minister Winston Churchill—groaned and begrudgingly drank it. He much preferred champagne, or scotch and soda, or brandy, or whiskey, or a fine wine, really anything but the kind of cocktails—usually some variation of a gin martini—that the President prepared for his guests each evening. In fact, he called them “filthy” and later joked, “The problem in this country is the drinks are too hard and the toilet paper’s too soft.”

It was days into Churchill’s three week stay at the White House from December 22, 1941, to January 14, 1942. At the beginning of his stay, the United States was still strategically adrift from its overnight entry into war. At the end of Churchill’s stay, he and President Franklin D. Roosevelt had concocted a plan to overrun the Nazis in Europe, defeat the Japanese in the Pacific, win the Second World War and preserve democracy on Earth. It was perhaps modern history’s most herculean task—and one that both men felt they were uniquely suited to undertake.

Both Churchill, 67 at the time, and Roosevelt, 59, had been children of their country’s aristocracy. Churchill’s father had served in the House of Commons and as India’s Secretary of State; his mother was a Brooklyn-born American socialite. Neither parent ever paid attention to Winston, nor showed much interest in him at all. As a refuge, young Winston threw himself into his country and his family’s history, which often overlapped. He had descended from the first Duke of Marlborough, John Churchill, who was rewarded with a magnificent estate in 1704, Blenheim Palace, where Winston was born 170 years later. Most of his ancestors had been politicians or magistrates of some kind. His signature walking stick had been a wedding gift from King Edward VII. Despite spurts of success and then failure, he always assumed that one day his moment would come—that he alone would defend the United Kingdom from its potential fall. The day he assumed his office at 10 Downing Street on May 10, 1940—just days before France fell to Germany and four months before the Blitz began—he felt that awesome vision become reality. As he wrote that day, “I felt as though I was walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial.”

Roosevelt, not to be outdone, had first visited the White House when he was just five years old in 1887, when Grover Cleveland was president. Cleveland, haggard from a long day, had told the young boy, “My little man, I am making a strange wish to you. It is that you may never be President of the United States.” When FDR married his wife Eleanor, in 1905, then President Teddy Roosevelt walked her down the aisle. When Franklin himself spent his first night in the White House as President, Eleanor recalled that “he behaved exactly as though he had always been there and never anywhere else.” By the time of Churchill’s visit, Roosevelt had already saved the nation from the Great Depression and remade it by enacting the New Deal.

But for both, the greatest task was yet to come.

Since Churchill had become Prime Minister he had tried to gain the United States’ official entry into World War II. And despite Hitler’s aggression—his invasion of Poland, the fall of France, the loss at Dunkirk, The Blitz—Roosevelt demurred, ever aware of the isolationist feelings in the United States that only grew after World War One. In fact, he had signed four separate Neutrality Acts in 1935, 1936, 1937 and 1939. The acts had been inspired partly by a committee led by Senator Gerald Nye (R-ND), which held 93 hearings from 1934 to 1936 to investigate whether WWI had been orchestrated by the arms industry and bankers who many Americans believed had lied America into war for profit. A Gallup poll conducted in May 1940 indicated that just 7% of Americans believed America should declare war on Germany and send troops abroad—meaning that a staggering 93% felt otherwise. In was an American tradition: since Washington’s farewell address in 1796, Americans had held true to the tenets of isolationism. But slowly, the veil of insulation began to lift. In March 1941, the Lend-Lease Act was signed into law, to provide materiel to Britain, the Soviet Union, France, Republic of China and other Allied nations.

But then came December 7, 1941.

That morning at 7:48 AM local time, the aquamarine blue skies of Oahu darkened into ashen gray when 353 Japanese aircraft appeared, launching an attack on the American base at Pearl Harbor, killing over 2,400. The United States was at war. Upon hearing the news on the BBC’s 9 PM broadcast, Churchill immediately called Roosevelt. “Mr. President, what’s this about Japan?” he asked. Roosevelt told him: “They have attacked us at Pearl Harbor. We are all in the same boat now.” Despite his outward dejection, inside Churchill rejoiced. In later writings, Churchill recounted his immediate reaction to Pearl Harbor and America’s entry: “We had won the war.”

Not everyone shared Churchill’s confidence. The Prime Minister wrote at the time, of Americans: “Some said they were soft, others that they would never be united. They would fool around at a distance. They would never come to grips.” To test his theory—that American entry alone would lead to victory in both Europe and the Pacific—Churchill wrote Roosevelt on December 9 to suggest that he visit Roosevelt, to “review the whole war plan.” In a reply, Roosevelt agreed. On December 11, Nazi Germany declared war on the United States—the only country it officially declared war against. On December 13, at 12:30PM, Churchill boarded the 45,000-ton battleship, Duke of York, and set course for America.

First, he would have to deal with gale-force winds and the threat of German U-boats below, which forced the ship to sail most of the trip at 6 knots—or, around 7 MPH. The massive waves, constant creaks, lack of ventilation and battened down deck led nearly every passenger to experience horrendous sea-sickness. Churchill later wrote, “However, once you get used to the motion, you don’t care a damn.” During the 9-day journey, Churchill wrote 7,000 words on his three war plans: “The Atlantic Front,” “The Pacific Front,” and “1943” (despite the fact that 1942 was still days away). The purpose for the trip, however, was much more concentrated: Germany First. That was his aim—to direct the United States away from focusing solely on retaliating against Japan and instead, steering its crosshairs to Hitler. As Churchill later wrote, “It was evident that, while the defeat of Japan would not mean the defeat of Germany, the defeat of Germany would infallibly mean the ruin of Japan.” Along with the plans, he also read two novels—C.S. Forester’s Brown on Resolutionand Frederick Britten Austin’s Forty Centuries Look Down. He also watched a movie every night, his favorite of which was Blood and Sand, about bullfighting.

Upon his arrival at the White House shortly after 3 PM on December 22, Churchill’s next task was to pick a bedroom. He went throughout the house, checking on each bed’s comfort and eventually settled on what is today known as the Queen’s Room, located on the second floor across the hall from the Lincoln Bedroom, where the President’s principal advisor Harry Hopkins had lived since the previous May. The next day, he and Roosevelt got to the work of planning the road ahead.

Roosevelt and Churchill had met twice before. Once that August aboard the USS Augusta off the coast of Newfoundland—and once on July 29, 1918 at Gray’s Inn in London. Back then, Roosevelt had been the Assistant Secretary of the Navy and Churchill then Britain’s Minister of Munitions. However, Churchill paid little attention to Roosevelt and Roosevelt came away little impressed himself. 23 and a half years later, the two were eye to eye, charting the course of the free world.

On Christmas Eve, Churchill spoke at the lighting of the National Christmas Tree alongside Roosevelt. He told the crowd, “I spend this anniversary and festival far from my country, far from my family, yet I cannot truthfully say that I feel far from home.” And it’s true—Churchill felt at home. He would regularly wander into the President’s bedroom to discuss the day’s meetings. After dinner each night, the two would meet again and as Eleanor later recalled, “We had to have imported brandy after dinner,”

along with Churchill’s customary Cuban cigars. Once, Roosevelt wandered into Churchill’s room to find him naked, to which Churchill quipped, “The Prime Minister of Great Britain has nothing to conceal from the President of the United States.”

On December 26, Churchill gave an address to a Joint Meeting of Congress. To his dismay, the heart palpitations he had mistaken for nerves two nights prior during his Christmas Eve speech had continued. After conferring briefly with Roosevelt upon his return to the White House about his speech, Churchill retired to his room, where finding it stuffy, he opened a window. “In trying to open the window, I strained my heart slightly, causing unpleasant sensations which continued for some days,” Churchill later wrote. In reality, he had likely suffered a minor heart attack. A doctor suggested six weeks of bed rest. Churchill refused—two days later he journeyed to Ottawa for a speech to Canadian Parliament, returning to the White House on New Year’s Eve.

The next day—on January 1, 1942—Churchill finally achieved the goal he had hoped for when he set sail for America on December 13. He, Roosevelt, the Russian Ambassador, and the Chinese Ambassador all committed to the Atlantic Charter, which had been crafted the previous August. It was called the Declaration by United Nations, a phrase Roosevelt had coined himself. As part the United States’ agreements with Britain, it would pursue “Germany First.” Churchill was overjoyed. Hitler had exactly 1215 days to live.

Still further planning went on—and Churchill’s hours began to weigh on the President. “The routine was beginning to get Roosevelt down,” one aide recalled. Roosevelt “remarked that he was looking forward to the Prime Minister’s departure in order to get some sleep.” Harry Hopkins confessed, “to have Winston here more than twice a year would be very exhausting.” Churchill recalled, “My American friends thought I was looking tired and ought to have a rest.” It was true—and they suggested he spend time near Palm Beach, where Lend-Lease administrator Edward R. Stettinius had a home. There, Churchill carried on the same routine—except for the fact that Churchill took to swimming naked every afternoon. An aide suggested swimming trunks, and that he might be seen. The Prime Minister replied, “If they are that much interested, it is their own fault what they see.”

On January 14, after his Florida excursion, Churchill left Washington. Roosevelt went along to see him off. As a gift, the Prime Minister gave the President a copy of his book, The River War. He inscribed it, “In rough times. January 1942.”

Looking at it, Roosevelt told him, “Trust me. To the bitter end.”

Sources:

William Manchester. The Last Lion. Vols I & III.

Jon Meacham. Franklin and Winston. 2003.

Andrew Roberts. Churchill: Walking With Destiny. 2018.

Wonderful history lesson! It clearly illustrates some background surrounding our close ties with Great Britain. Thank you!

What a great piece of writing, Tim! Thank you!!!