Democrats needed a new direction.

They had given the same answers again and again but the problems on the test had changed. It was a lesson on how political ages come to an end: a party keeps winning, or when it loses, loses barely. And over time, that party develops a feeling of assurance, that their way of thinking is correct, because in the past, it has been correct. This is how dominant ideologies within political parties work: they employ a class of people who, in a sense, get lucky. They advise a candidate who wins, they gain power, they keep the power, and their ideas and tactics atrophy over time.

Such was the case last week in 2024, and such was the case in 1992.

In 1992, the Republicans’ success caught up to them. Like Democrats in 2024, the Republican Party by then had controlled the White House for 12 of the prior 16 years—and their ideas and understanding of Americans’ attitudes were based around the same premises discussed in the same meetings with the same people whose hair increasingly thinned and grayed over time.

That year, the President George H.W. Bush was out of touch. He had won a term of his own in 1988 because of the associations voters made with the president he had served as Vice President, Ronald Reagan. Reagan had been the Republican Übermensch, moving the conservative revolution further right and establishing the GOP as the party of corporate profits, low taxes and incredibly effective fearmongering. Most importantly to donors and the consultant class, Reagan won in two landslides in 1980 and 1984. By 1988, a still unsure-of-its-self Democratic Party nominated Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, who like the prior Democratic nominee, former Vice President Walter Mondale, was easily characterized as weak and fanatically liberal.

In 1992, Republicans went back to the well, even as the nation began to face economic headwinds and a recession. In electoral politics, the economy is the constant. It’s like bread in a sandwich. If you have shitty bread, you have a shitty sandwich. There is no getting over that. But, because it’s always there (and either a positive or negative factor), it is not always the thing that shifts an election. But in 1992—despite the long-lauded ethos of James Carville—it wasn’t the economy. It was the culture, stupid.

A new kind of campaign was evolving.

On June 2, Bill Clinton won the California Primary and five other states, securing enough delegates to wrap up the Democratic nomination. The day before the primary, Clinton had a three-airport day, doing in-person interviews in California’s major media markets. It was what Time columnist, Walter Shapiro, called “the kind of old-fashioned campaign day that probably should be preserved in amber and sent to the Smithsonian,” noting acutely that “as [Ross]Perot has demonstrated, presidential candidates no longer have to put their bodies on the line like this to get TV attention.” At that moment—in early June 1992—polls indicated that Ross Perot, the Texas billionaire, was in the lead over Clinton and President Bush. Perot had launched his campaign on Larry King Live, where he was a frequent guest in the years prior. Amazingly, Perot—who had never been in politics—seemed to know the layout of the media ecosystem in 1992 better than his seasoned opponents.

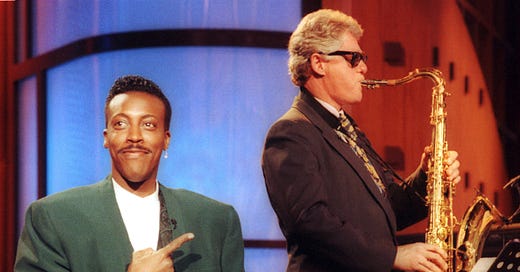

Clinton, now comfortably the nominee, began to figure that out too. The day after the California primary, rather than going to meet with editorial boards or sit down with a network, Clinton appeared on The Aresenio Hall Show. Hall’s show had debuted in 1989, targeting a younger audience than other late-night programming. The previous month, on May 22, 1992, The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson aired its last broadcast, after three decades on NBC. Arsenio Hall was new: 36 years old, he had hosted the MTV Music Video Awards for three years in a row, he had starred in the smash-hit Coming to America with Eddie Murphy, and he was the first Black host in the history of late-night television.

At the beginning of every show, the announcer Burton Richardson would announce Arsenio Hall, holding out the “O” in Arsenio before gasping out “HALL!” as the host appeared. And in usual late-night fashion, the house band would play. But on this particular night, the band had a guest: Governor Clinton on saxophone, busting out a solo as the band played an instrumental version of “Heartbreak Hotel.” Clinton, still bruised with well-founded accusations of infidelity throughout the primary, seemed to be steering into the skid rather than out of it. He was running to be the youngest president since John F. Kennedy and at 46, he looked young compared to his two opponents, who were both well into their 60s. Wearing Blues Brothers-esque sunglasses he borrowed from an aide and a blue and yellow flowered tie borrowed from the show’s costume department, Clinton looked the part. During a rehearsal for the show, Clinton had told the band, “if I screw up, play louder.” But Clinton played the part too, acquitting himself more than well enough on the sax.

As Hall and Clinton made their way to the main set and sat down across from one another on comfortable, slate gray armchairs, it was clear Clinton—or the image he was projecting—was at ease. Even when asked about the “smoking the joint thing” by Hall, Clinton brushed it off with candor, responding, “I did my best, I tried, but I just couldn’t inhale it…it was another one of those things I tried to do and just failed at in life.” Clinton had both the crowd and Hall laughing. He continued, “I got more publicity on that than my idea to send every kid in America to college who wants to go, which I think is more important to the election and to the future of this country.” The crowd’s laughter turned to applause. Hall then asked if he could address “what you’ll do for the economy, that’s part of the LA riots and some of the other frustrations all over this country.”

Clinton quickly seized the opportunity. He talked about how America needed to invest in its people and its young people. He linked the issue directly to Hall, who earlier in the show had spoken about his pastor, whom Clinton also knew. “All those people that you and your pastor try to help, if you could tell them when they’re 11, 12 years old, look, if you stay straight you may not make as much money as you would dealing drugs but you’re gonna make enough money. You’re gonna have a good decent life.” He continued, listing off ideas for a “peace corps here at home” as the crowd applauded, declaring, “a lot of these kids in trouble, they’re never the most important person in the world to anybody, except the people they’re in the gangs with. So, we gotta give them a good gang to be a part of and you gotta have some kind of personal connection.”

Just days later, on June 13, Clinton addressed the Rainbow Coalition at an event hosted by the Reverend Jesse Jackson—a scene I wrote about in detail on this page in August, where Clinton attacked a rapper named Sister Souljah for making racist comments, in turn attacking liberal Democratic orthodoxy itself. At the time, Sister Souljah was barely a minor celebrity, without much of an audience, radio play, or chart success. But Clinton used her comments as an opportunity to take on a story that was in a very real sense, a media creation in and of itself. Clinton simply cashed in on it and used the opportunity to trash the left wing of his party and the Reverend Jesse Jackson. Two days after that, he appeared on MTV’s “Chose or Lose” election special, a town hall style event in which young people asked Clinton questions, the first very of which addressed the Sister Souljah comments made just days prior.

In just a few days’ work, Clinton made clear that he had learned from Perot, and saw, through the heart of the American cultural apparatus, his path to the White House. And it worked: he broke the back of the Reagan coalition and won in 1992 by turning his back on over 30 years of Democratic orthodoxy, running as a tough on crime candidate who sought common sense solutions on immigration and who promised to “end welfare as we know it.” In a sense, he captured the party by running against it, much like his wife’s future opponent did in 2016 with the Republican Party.

In 2024, the Obama Coalition, much like Reagan Coalition before it, came to an end. The reason Democrats lost in 2024—like Republicans in 1992—was not simply economic, although again, that was and always is a major factor. The distinguishing difference was cultural. Democrats in 2024 did not understand how to talk like normal people and meet folks where they were.

Remarkably, that was reflected in similar winning coalitions in 1992 and 2024. Among those with a high school degree or less, Clinton won 55% of voters in 1992; Trump won 59% in 2024. In 1992, 45% of college graduates voted for Clinton; in 2024, 46% went for Trump. In 1992, Clinton lost by 12 percentage points to Bush among voters who made more than $75,000; in 2024, Trump lost by 11 percentage points to Harris among voters who made more than $100,000. In essence, the parties swapped on who represented the working class and who represented the elites in the United States.

In 2024, talking down to voters to tell them that the economy was actually good, or the President was actually fine, or Vice President Harris was actually culturally in touch because someone called her “Brat” wasn’t just out of touch, it was an elite-driven lie. The dominant media class and Democratic elite in 2024 missed the cultural zeitgeist by an even larger margin than Harris lost by. It was a landslide of delusion.

In 1992, it wasn’t solely the fact that Clinton went on Arsenio Hall or MTV that brought him electoral success, or that he and his advisers understood the culture better than their opponents, although that certainly helped. It was that Bill Clinton was good. He was likable, authentic, able to banter, give it and take it, all while being in on the joke that had at times slipped into lies and other improprieties.

Reminds me of another candidate who has found success recently.

Sources:

https://www.wsj.com/politics/elections/election-2024-voters-demographics-votecast-survey-5a21c604

When the Dem party turned on women with Billy, the heart throb, it led directly to trump. White supremacy on the march.