In the bottom of the first, Johnny Sain dug into the rubber and readied himself for his first start of the season. It was a cold, crisp mid-April day with a perfect blue sky. Sain had been born in Havana, Arkansas, a rural town near the center of the state that had a population of less than 500 when he was born. He had debuted with the Boston Braves in 1942, throwing 97 innings that mostly came in relief and late that year—like so many other young American men—he joined the U.S. Navy. For the next three years, Sain served as a pilot, forgoing his baseball career to serve his country. In 1943, Sain had participated in a Red Cross exhibition game at Yankee Stadium and had pitched to Babe Ruth, then 48, in his very last plate appearance in an organized game. Ruth walked. Now, on April 15, 1947, Sain was back pitching for the Braves. After retiring leadoff hitter Eddie Stanky on a groundout, Sain dug in again to face a hitter making his Major League debut: Jackie Robinson.

Robinson and Sain had a lot in common. Robinson had been born in Cairo, Georgia, less than 800 miles from Sain’s hometown, and had also joined the Armed Services in 1942 as the Second World War intensified. But crucially, they had one distinct difference that had kept the two from ever going to the same school, drinking from the same water fountain, serving in the same battalion, or up until that moment, playing on the same field. Sain was white, and Robinson was Black. Now, playing first base and hitting second for the Brooklyn Dodgers, Robinson was doing what no Black American had ever done: he was playing in a Major League Baseball game, the first player to break baseball’s color barrier.

Branch Rickey, the general manager for the Dodgers, had signed Robinson to a professional contract on August 28, 1945. Robinson had been a standout athlete at UCLA, where he lettered in football, basketball, baseball, and track. After the war, he had signed with the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues, then the only avenue for Black players. The Monarchs had long been the team of Satchel Paige, one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history, who like every other great Black player, had never played against Major League competition. But Rickey wasn’t looking for Paige, or any of the other now-aging greats like Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, or Cool Papa Bell. Rickey wanted someone who, as he said, had “the guts not to fight back” against the racism he would inevitably face. And after playing the 1946 season for the Dodgers’ minor league affiliate, the Montreal Royals, Rickey decided Robinson was ready.

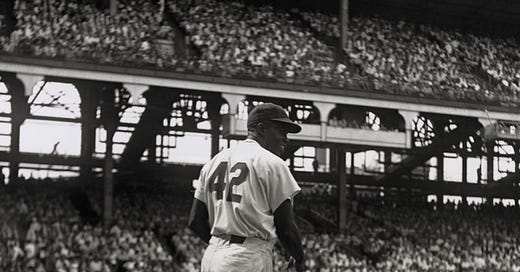

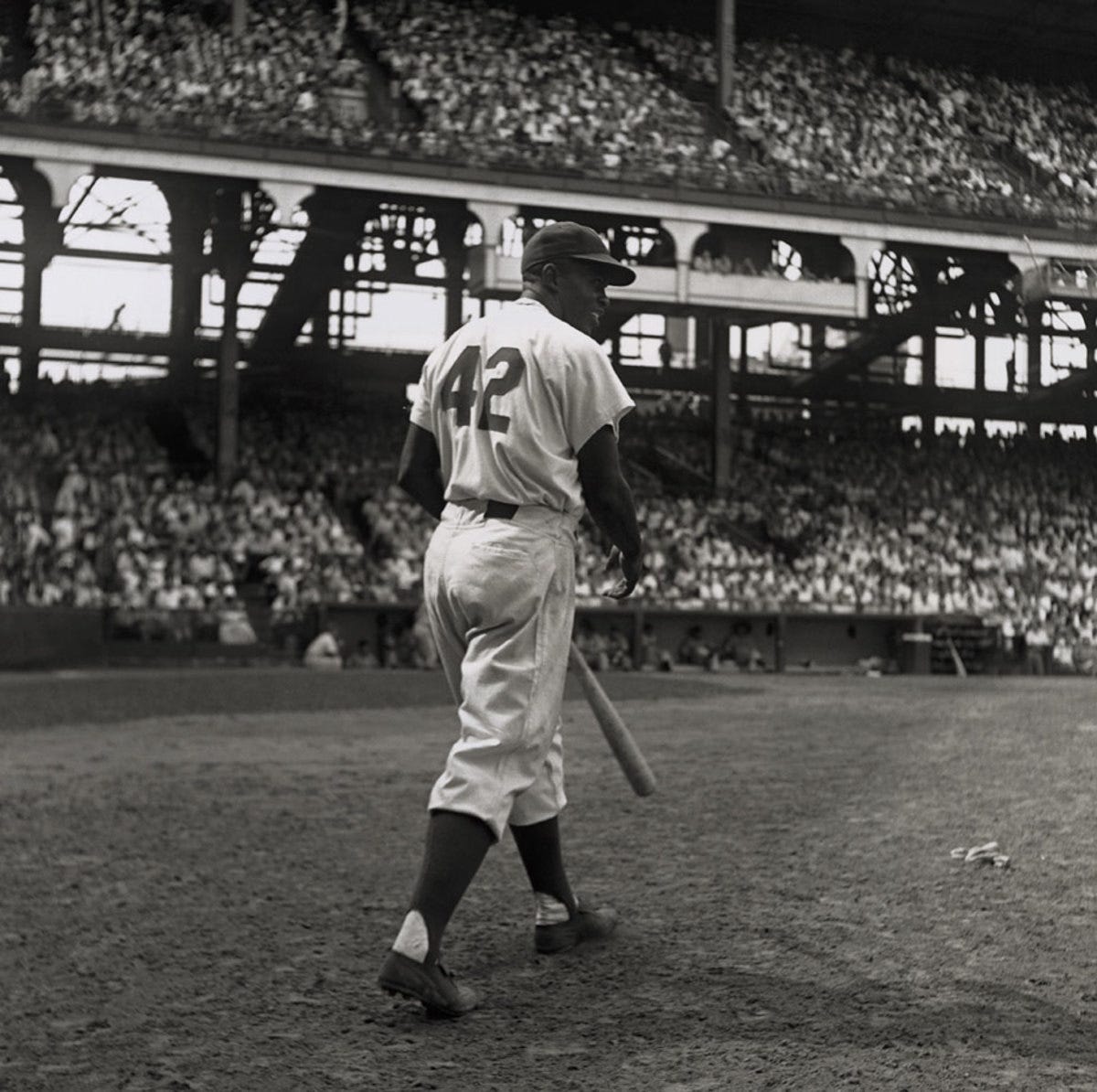

That morning on April 15, Robinson had awoken inside Manhattan’s McAlpin Hotel to the cries of his five-month-old son, Jack Jr., being eased back to sleep by his wife, Rachel. By 9 AM, he was out the door, dressed in a suit and tie and camelhair coat. Before he left, Robinson turned to his wife and said, “Just in case you have trouble picking me out I’ll be wearing number forty-two.” After entering the clubhouse inside Ebbets Field, Robinson found that—unlike the rest of the players—he did not yet have a locker. Instead, his crisp white uniform hung on a hook on the wall. Few players came over to greet him, save for Ralph Branca and Gene Hermanski, who shook his hand and said how glad they were to have him.

Rachel Robinson, too, had problems that morning. She left the hotel at about 11:30 AM, with her baby in tow, and had trouble hailing a cab. Worse, Jack Jr. was sick—she had to hail down a hot dog vendor to help heat his formula as first pitch neared. Still, alongside 26,622 others, she watched as her husband made history. The game’s first batter, Dick Culler for the Braves, grounded out to Dodgers’ third baseman, Spider Jorgensen, who threw to Robinson at first. As the ball hit Robinson’s mit, his appearance in the game became official, breaking baseball’s color barrier. Still, Robinson had to hit. And as he later wrote, it did not go as he had hoped. “I did a miserable job. I grounded out to the third baseman, flied out to left field, bounced into a double play, was safe on an error, and, later, was removed as a defensive safeguard.”

Still, this was April 15, 1947—and that day, Jackie Robinson did a lot more than go hitless in his first Major League game. He took steps that arguably started the Civil Rights movement that defined the ensuing two decades. At that moment, President Truman’s decision to desegregate the military was still more than a year away. Brown v. Board of Education would not be decided until May 17, 1954. Rosa Parks would not refuse to give up her seat on the Montgomery city bus until 1955 and the Little Rock Nine wouldn’t be marched into school alongside the National Guard for a decade. This was the moment—as Robinson dug in against Johnny Sain—that America changed forever.

Little of that was on Robinson’s mind in the moment. He was a ballplayer, and ballplayers want to get hits. And in his first twenty at bats, he was hitless. Still, the Dodgers’ manager, Burt Shotton, stuck with Robinson even as the external and internal pressure built. Eventually, Number 42 broke out. That season, he would lead the National League in stolen bases, hit .297, and score 125 runs. At the end of the season, he was named the Rookie of the Year and finished fifth in the MVP balloting. Considering all that he had to endure—the hate of opposing players, fans, people on the street, even some teammates—it is one of the greatest seasons in baseball history.

Today is Jackie Robinson Day in Major League Baseball. Across the sport, every player will wear the number 42. But in 2025, for the most part, remembrances about Robinson like this one are considered the devil’s work of “D.E.I.,” a “woke” retelling of history meant to cast a shadow on some version of America that never existed. Until recently, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth—who has made eliminating D.E.I. his chief task rather than, you know, serving American troops in uniform—had the Pentagon remove all traces of Robinson from its website. After several people, including ESPN’s Jeff Passan, noticed the discrepancy, the Pentagon corrected its error. Only after it was caught, of course. The reason is that these people who pretend to uphold “American values” do not like America. They like their version of it. They don’t care for the nation’s history or its people. To them, stories of pain, of overcoming obstacles, and of ultimate triumph are too messy, too complicated, too real. They would rather erase history’s best stories rather than be forced to tell them.

Sources:

42 - As American as baseball!

I was blown away to see his widow in the Mets clubhouse today, she’s 102 and still getting out in a wheelchair to honor her husband. What an amazing woman!